Shining a Light on Gender Identity Services: How The Cass Review Shows The Need For Evidence-Based Paediatric Medicine (Dr Julie Maxwell)

Read in PDFSummary

Over recent years there has been an explosion in the numbers of children and young people identifying as transgender, and widespread acceptance of a belief in gender identity as something separate from biological sex. The idea that someone’s innate sense of their own gender determines whether they are male or female – or some other gender identity – has led to the use of medical and surgical pathways designed to alter a person’s body to fit with how they feel.

In the medical world this phenomenon has been approached in a very different way to other comparable conditions (e.g. body dysmorphia and anorexia). The treatment pathway which had become widely accepted in NHS gender services as well as in private clinics had not followed usual clinical practice and was disconnected from the evidence base. The medical approach has too often been based on a ‘social justice’ model rather than the empirically-led process that is more typical of the NHS.

The Cass report uncovers the way in which a vulnerable and distressed group have not received the same quality of care as other children and young people who are experiencing distress that is not gender-related. It highlights the many ways in which not following standard medical and safeguarding procedures has led to many children not receiving the best standards of assessment and treatment.

Introduction

The 10th April 2024 marked the release of the long-awaited final report from what has become known as the Cass Review. It was accompanied by numerous (mostly positive) headlines across a variety of media, although very little coverage by the BBC.

This comprehensive report marked the conclusion of a review into NHS gender identity services for children and young people. In 2020 NHS England and NHS Improvement announced that they had commissioned this independent review to be led by Dr Hilary Cass OBE (a retired Paediatrician and previous president of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health).

The full report [1] is 388 pages long and probably only read by those with keen interest but the overview and summary of recommendations would be of interest to many. Useful summaries have also been provided by the British Medical Journal [2] and the Bayswater Group [3].

The terms of reference for the review [4] state its rationale:

‘In recent years there has been a significant increase in the number of referrals to the Gender Identity Development Service, and this has occurred at a time when the service has moved from a psychosocial and psychotherapeutic model to one that also prescribes medical interventions by way of hormone drugs. This has contributed to growing interest in how the NHS should most appropriately assess, diagnose and care for children and young people who present with gender incongruence and gender identity issues.’ [5]

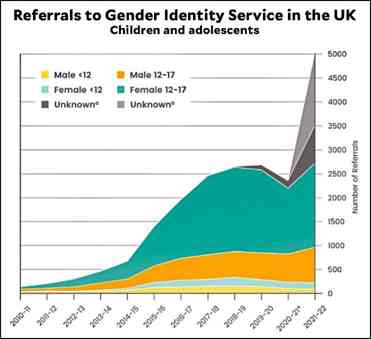

This graph shows referrals to the Gender Identity service (GIDS) in the UK based at the Tavistock Clinic and highlights the very significant increase since the clinic opened and in particular since 2014. It should be noted in particular that by far the biggest increase has been in teenagers and specifically teenage girls.

The change in the way these children were managed was also significant – as the terms of reference say there was a move from a psychosocial and psychotherapeutic model to one that increasingly included medical interventions. The medical intervention starts with drugs which are given as the child enters puberty to block the changes of puberty and then at 16 the child moves onto opposite sex hormones which cause some of the external changes of the opposite sex to occur.

Before I move on to look at what the review says about these two aspects we need to consider some of the reasons why the review took so long and why it was such a struggle for Dr Cass and all those involved.

Toxic debate

Dr Cass comments several times in the report on the toxicity of the debate – she says ‘the toxicity of the debate is exceptional’ [6] and that the ‘increasingly toxic, ideological and polarised public debate has made the work of the review significantly harder and does nothing to serve the children and young people [affected]’. [7] She also comments on how the ‘inflexibility of the factional opinion and resulting toxicity of debates’ [8] affects gender-questioning young people. The toxicity also touches clinicians – Dr Cass states, ‘There are few other areas of healthcare where professionals are so afraid to openly discuss their view, where people are vilified on social media, and where name-calling echoes the worst bullying behaviour. This must stop.’ [9]

Lack of follow-up data

In addition to the toxic nature of the debate and the silencing of anyone who raised questions or concerns there were problems in trying to obtain evidence and data regarding outcomes of children treated at GIDS. Dr Cass discovered that many children had been issued with new NHS numbers making it difficult to track them into adult services. Although legislation was made to resolve this, an extra difficulty was that 6 out of the 7 adult clinics refused to share their data. They have since been ordered to do so by NHS England and their services will also be examined. Dr Cass states in the review that, ‘there continues to be a lack of high-quality evidence in this area and disappointingly… attempts to improve the evidence base have been thwarted by a lack of cooperation from the adult gender services’. [10]

The Final Report

The report was finally published, although it took much longer than planned and without access to all evidence and data that it should have had. It is generally scathing of the treatment that children who are questioning their gender have received. This has been based on a social justice model rather than the usual practice for the NHS which would be evidence-based. The toxic debate has also made many clinicians fearful of working with any child who has questions about their gender leading them to receive almost no support at all.

The report contains 5 main sections, on the:

- Approach which looks at how the review was undertaken;

- Context which outlines how the Gender Identity Services developed and why the review was commissioned;

- Understanding of the patient cohort which goes into the details of the change in patient profile and some of the factors in society which may have influenced this;

- Clinical approach and management which describes diagnosis and management along with details of the evidence base (or lack thereof) on which social and medical transition is based;

- Service model – this is a technical section looking at a new service model for services for children who are questioning their gender.

Overall the report contains 32 recommendations (the summary and recommendations alone cover 25 pages but are definitely worth reading). So what does the report say about the two aspects mentioned earlier?

Increase in numbers

Not only was there a huge increase in referrals particularly from 2014 onwards but there was a shift in those being referred from younger children (previous research [11] showed that for most of these children the gender dysphoria would resolve as they went through puberty) to teenagers who also had a greater complexity of co-occurring mental health problems, neurodiversity (Autism and ADHD) and adverse childhood experiences.

The report looks at some of the factors that might be contributing to this rise in children questioning their gender as well as the overall increase in mental health difficulties in children and adolescents that we are seeing. One of the biggest differences we see in this generation compared to previous ones is near constant access to the on-line world and particularly social media. This exposes children with underdeveloped brains to social media which promotes often unrealistic ideas of what men and women should look like not to mention sexually explicit material and pornography.

The report expresses concerns that many parents hold about ‘online information that describes normal adolescent discomfort as a possible sign of being trans and that particular influencers have had a significant impact on their child’s beliefs and understanding’. [12] In addition, the issue of ‘diagnostic overshadowing’ [13] is highlighted – this is when the focus becomes solely on gender and ignores other complex issues that might also be present and therefore do not get addressed.

Medical intervention

Usually in medicine there is a very cautious approach to the introduction of new treatments (especially in paediatrics). The review highlights that ‘Quite the reverse happened in the field of gender care for children’. [14] So instead of a cautious evidence-based approach to treatment the use of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones became standard practice in children with gender dysphoria despite lack of evidence for their effectiveness or safety. The review states, ‘The adoption of a treatment with uncertain benefits without further scrutiny is a significant departure from established practice’. [15] The review is clear that especially given the complexity and vulnerability of this group of young people they should be treated in services which operate to the same standards as other services treating such complex young people.

Not only is there no good evidence to support the long term benefits of a medical route for children who are questioning their gender but previous evidence shows that questions around gender will only persist in a minority and it is not possible to predict which children these will be.

As a result we are seeing an increase in young adults coming forward who, having undergone varying degrees of transition, wish to return to living as their biological sex or realise too late that no amount of medical or surgical intervention can actually make them the opposite sex. These detransitioners often express sadness and anger at those who allowed or enabled them to go down a pathway of ‘transition’. This brings us to one final aspect we must mention:

Social transition

Social transition is where a person adopts social changes such as altering hair or clothing, name change and / or different pronouns to appear as the opposite sex. Many children have already undergone social transition before entering any kind of medical or mental health services and it is often seen as being the kind thing to do to reduce distress.

The systematic scrutiny of the Cass Review showed no clear evidence of any effect on mental health (either positive or negative) of these practices, but did seem to make it more likely the child would proceed to a medical pathway. [16] Social transition is a significant psychological intervention and should never even be considered without involving medical professionals and certainly should not be undertaken by schools without parents’ knowledge.

The recent pastoral reflection by the Catholic Bishops of England and Wales [17] reminds us that we are created by God – male and female:

‘For you formed my inward parts; You knitted me together in my mother’s womb, I praise you, for I am fearfully and wonderfully made. Wonderful are your works; My soul knows it very well. My frame was not hidden from you, When I was being made in secret, Intricately woven in the depths of the earth.’ [18]

‘So, God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.’ [19]

‘God saw everything that he had made, and indeed, it was very good.’ [20]

The Bishops’ reflection also resonates with what we see in the Cass Review report:

‘With regard to children and young people, across society and within the Church, there are some who experience gender incongruence / dysphoria. From a pastoral perspective, accompaniment must have at its heart an acceptance and celebration of the body as created, respect for parents as primary educators, and should uphold best practice in terms of safeguarding principles. Medical intervention for children should not be supported. It should also be recognised that social ‘transition’ (living in the opposite gender role) can have a formative impact on a child’s development and can set a child on a path towards later medical interventions. Care should be taken to avoid this especially with young children.’ [21]

Children who are questioning their gender need our love, support and prayers as we seek to walk with them in their distress. The loving thing to do in the long term is not to encourage them to socially transition or avoid puberty but to help them to understand the goodness of God’s creation, the purpose of puberty being to grow into men and women (different but equal) and that distress may be part of growing up and God’s way of shaping us into adulthood.

Endnotes

[1] Cass Review. Independent review of gender identity services for children and young people: Final report, April 2024:

https://cass.independent-review.uk/home/publications/final-report/

[2] K. Abbasi, ‘The Cass review: an opportunity to unite behind evidence informed care in gender medicine’ BMJ 2024; 385 doi:

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.q837

[3] Bayswater Support Group statement on the final Cass Review report, 14 April 2024:

https://www.bayswatersupport.org.uk/statement-final-cass-review/

[4] Terms of Reference for Review of Gender Identity Development Service for children and adolescents (September 2020):

https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/GIDS_independent_review_ToR.pdf

[5] Ibid., para. 2.

[6] Op. cit., Cass Review, p. 13.

[7] Ibid., p. 20.

[8] Ibid., p. 67.

[9] Ibid., p. 13.

[10] Ibid., p. 20.

[11] Kaltiala-Heino R, Bergman H, Työläjärvi M, Frisén L. Gender dysphoria in adolescence: current perspectives. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2018 Mar 2;9:31-41. doi: 10.2147/AHMT.S135432.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5841333/

[12] Op. cit., Cass Review, p. 120.

[13] Ibid., p. 200.

[14] Ibid., p.13.

[15] Ibid., p. 25.

[16] Ibid., p. 31.

[17] Catholic Bishops Conference of England and Wales. Intricately Woven by the Lord: A pastoral reflection on gender by the Catholic Bishops of England and Wales (March 2024):

[18] Psalm 139. 13-15.

[19] Genesis 1.27.

[20] Ibid.,1.31.

[21] Op. cit., Intricately Woven, p. 10. Cf. Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, Dignitas infinita, 55-60:

See also D.A. Jones, Gender dysphoria: Some Catholic bioethical reflections, Anscombe Bioethics Centre, 21 May 2017:

Most recent

A Human Right to Suicide Prevention: Analysis of ‘The Impact of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill III’

03 June 2025

An Equal Opportunity to Live: Analysis of ‘The Impact of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill II’

03 June 2025

Ending Life as Cutting Costs: Analysis of ‘The Impact of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill I’ (Professor David Albert Jones)

23 May 2025

Sincerest Thanks for Your Support

Staff are grateful to all those who sustained the Centre in the past by their prayers and the generous financial support from trusts, organisations, communities and especially from individual donors, including the core funding that came through the Day for Life fund and so from the generosity of many thousands of parishioners. We would finally like to acknowledge the support the Centre has received from the Catholic community in Ireland, especially during the pandemic when second collections were not possible.

We would like to emphasise that, though the Centre is now closed, these donations have not been wasted but have helped educate and support generations of conscientious healthcare professionals, clerics, and lay people over almost 50 years. This support has also helped prevent repeated attempts to legalise euthanasia or assisted suicide in Britain and Ireland from 1993 till the end of the Centre’s work on 31 July 2025.