Bioethics in Brief: Abortion

Bioethics In Brief – AbortionAbortion may be defined as the deliberate killing, however performed, of the early human being (the foetus or the embryo). Such a definition is given in the encyclical Evangelium vitae (§58), and also sometimes by defenders of abortion, including doctors who perform abortions. Some will indeed quite bluntly say that the aim of abortion is to kill the foetus e.g. because the woman does not wish to be a mother. If the baby lives following removal from the woman, as sometimes happens with some abortions late in pregnancy, the abortion is seen as a failure since, although the woman is no longer pregnant, the child is still alive

Some defend abortion on the grounds that the foetus is not yet a ‘person’. By ‘person’ they mean a being with full moral status and / or a being who is self-conscious, with complex desires, etc., seen as relevant to moral status.

One objection to this view is that newborn babies are similarly lacking in self-consciousness and in complex desires. Most of us believe that newborn babies have full moral status: we reject infanticide as a solution to problems faced by parents, even serious problems of parents who are cut off from any outside source of help. Nor are self-consciousness and complex desires necessary to have a morally significant stake in one’s own future. As soon as a living human being exists, that individual’s stake in the future exists: the young individual may not take an interest in much, or in anything at all, but still has interests in his or her survival and well-being.

If I am a living bodily being, am I not the same bodily being who was conceived and later born? Or did that living being somehow disappear in between conception and birth? Human persons are not mere ghosts inhabiting bodies but are a unique kind of animal: a rational or spiritual animal, with the special moral status that involves. Just as a canary is a flying kind of being, even for canaries too young or sick to fly, so a human being is a thinking, choosing kind of being. Even babies who are unable to engage in rational behaviour during their lifetime, e.g. because they are brain damaged or terminally ill, are still members of the rational human kind, with rights and interests appropriate to that kind.

Morally, there is no such thing as a ‘subhuman human’ or human ‘non-person’: human beings are equal in their basic moral status, including their possession of morally significant interests. To say this is not to say that everyone’s interests can and/or should be promoted all the time. Rather, it is to say that everyone’s interests must be respected, and must not be unfairly attacked or impinged on. We cannot always save everyone we would like to save, but that does not entitle us to attack or assault an innocent human being, to try to benefit ourselves or someone else.

If the foetus is the same living human being who might later be born, then the woman is already the mother of that new human being. It is not necessary to choose to be a mother in order to be one – any more than it is necessary to choose to be a father in order to be one. Women and men become parents when they conceive, and both have parental duties to their child.

These duties are not identical for men and women, but may be quite onerous in either case – even if most people welcome their children as a great blessing once they are born. Men cannot become pregnant, but can be morally obliged to do difficult work, including hard physical work, to support their child, including a child they did not choose to conceive. Both men and women can ‘step up to the plate’ and be good parents even in challenging circumstances – though exceptionally where they are unable to care for their child themselves that can mean delegating their responsibility to others via adoption.

Some defenders of abortion will accept, if only for the sake of argument, that the foetus is an unborn child, a human person with full moral status. Even assuming this is true, they say, abortion would still be justified as no person has a right to the bodily support of another person. After all, we do not think that people are morally obliged to be bone marrow or organ donors, even if donation is necessary to save someone else’s life. This is an argument based on bodily autonomy, rather than on moral status.

To this it can be responded that even if being a live bone marrow or organ donor may be morally discretionary (and is not legal without consent of the donor), the support of pregnancy cannot be compared to this kind of medical support. Rather, it is basic care for a child, using a natural bodily function of the mother of a kind from which we have all benefited ourselves. Whereas organ donation involves the giving of organs that do not, strictly speaking, belong in someone else’s body, pregnancy is a joint enterprise. While the mother and the unborn child have distinct bodies, the maternal and the foetal placenta function as a joint organ, for example. The woman’s body is not being used for anything that it is not ordered towards. Pregnancy is thus more like breastfeeding an infant who will die if not breastfed than like anything more ‘high tech’.

Sometimes the argument from bodily autonomy is put forward in such a way that depicts abortion as little more than ‘disconnecting’ the baby from his or her mother (as in the famous violinist thought experiment of Judith Jarvis Thomson). But many if not all forms of abortion do not simply involve the withdrawal or ‘disconnecting’ of the woman’s bodily support, but involve deliberate and destructive interventions on the body of the unborn child. This goes beyond what the argument from bodily autonomy can claim. If the foetus is a human being with rights, does he or she not have a similar right to have his or her bodily integrity and autonomy respected?

Supporters of abortion who accept the full moral status of at least the developed foetus will sometimes argue that abortion is nonetheless morally acceptable at least sometimes for the sake of the unborn child. This may be because the child is ill or seriously disabled and abortion is seen as a form of euthanasia. It is stressed that the motive of the abortion is precisely to benefit the child by ending a life that will be painful or very limited. The parents are deeply grieved by the abortion but agree to it to benefit their baby.

Read the Bioethics in Brief entry on Euthanasia.

To this it can be responded that the disabled unborn child, like any disabled or non-disabled human being, has a life of value that must be respected. Apart from the general moral importance of all human beings as members of a rational kind of being, our life – our sheer physical presence as human individuals – has value simply in itself. We are valuable not just for what we do, but for what, or who, we are.

Healthcare professionals should not offer parents prenatal tests to screen out children with disabilities such that life is allowed to progress only conditionally on the child’s ability or state of health. Tests should be offered only where there is a realistic hope that these might benefit the child, for example by changing diet, closer monitoring of pregnancy or a specialised birth plan. For parents, as guardians, not owners, of their unborn child’s life, they should be wary of accepting tests that have no benefit to the child and which might lead to pressure from healthcare professionals to terminate the pregnancy. Where foetal disability has been diagnosed parents should be generously supported, including via the help and advice of disabled adults and parents with experience of having a disabled child. Where it is certain or likely that the unborn child will not survive long after birth, proper perinatal hospice care should be offered to parents, to allow them to spend quality time with their baby following birth, however short that time may be.

Most recent

Bioethics in Brief: The Status of the Human Embryo

16 April 2022

Our ‘Bioethics in Brief’ on the Status of the Human Embryo.

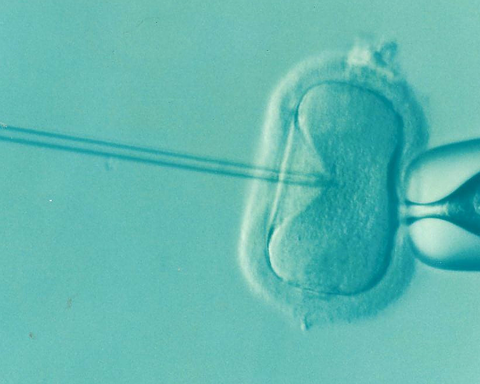

Bioethics in Brief: IVF and Artificial Insemination

16 April 2022

Our ‘Bioethics in Brief’ on IVF and Artificial Insemination.

Bioethics in Brief: Contraception and Natural Family Planning

16 April 2022

Our ‘Bioethics in Brief’ on the Contraception and Natural Family Planning.

Support Us

The Anscombe Bioethics Centre is supported by the Catholic Church in England and Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, but has also always relied on donations from generous individuals, friends and benefactors.