Evidence of Harm: Assessing the Impact of Assisted Dying / Assisted Suicide on Palliative Care (Professor David Albert Jones)

Read in PDFi. The aim of this paper is to examine critically the evidence given in support of the conclusion in the House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee 2024 Report on Assisted Dying / Assisted Suicide [AD / AS] that they ‘did not see any indications of palliative and end-of-life care deteriorating in quality or provision following the introduction of AD / AS; indeed the introduction of AD / AS has been linked with an improvement in palliative care in several jurisdictions.’

ii. This conclusion is based on selective evidence that the Committee received from respondents, not a comprehensive review of the literature. A more complete review of the evidence demonstrates that the conclusion is flawed in at least four ways: some evidence was not relevant, some was outdated, some was speculative, and there is more recent and better evidence that needs to be considered.

iii. The Report cites evidence about how many AD / AS recipients also received palliative care services. This is not relevant as these numbers say nothing about quality or adequacy of care or whether AD / AS helped or hindered the delivery of palliative care.

iv. The Report cites evidence about increased spending and provision on palliative care after introducing AD / AS based on out-of-date data from a single country (Belgium), with figures only available until 2011. More recent evidence tells a very different story:

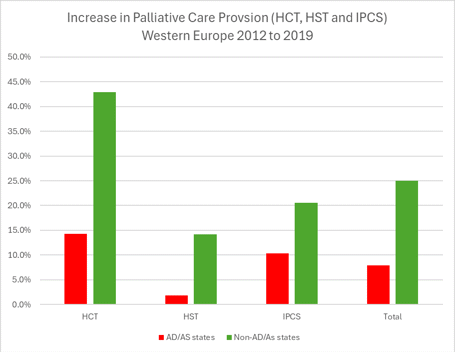

- Between 2012 and 2019 the four European countries with AD / AS (Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Switzerland) increased palliative care provision by 7.9%, while the twenty non-AD / AS countries in Western Europe increased provision by 25%.

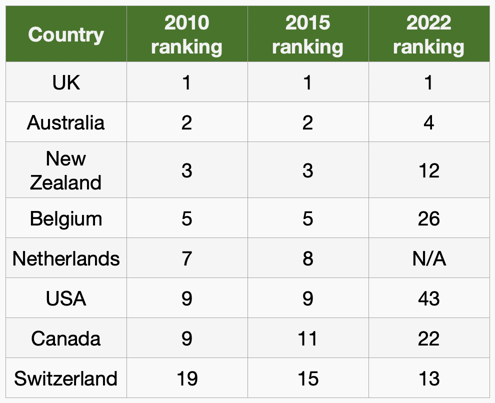

- Between 2015 and 2022, Belgium, Canada and the United States also fell out of the top quartile in the world ranking of quality of death and dying, while the United Kingdom remains in first place.

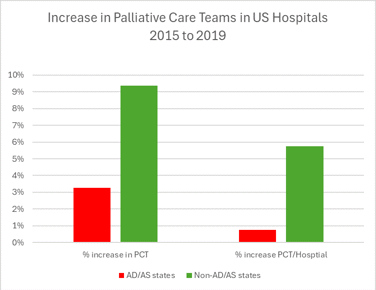

- Between 2015 and 2019 palliative care teams in hospitals increased by 3.2% in U.S. States with AD / AS while non-AD / AS States saw an increase of 9.4%.

The latest evidence thus shows that, while there have been improvements in palliative care in jurisdictions with AD / AS, comparable jurisdictions without AD / AS have made better progress.

v. Other evidence of increased spending on palliative care was speculative, being based on future commitments to spend money that were not fulfilled rather than on money actually spent:

- In Canada, $6 billion was committed to funding palliative care and home care over ten years at the time AD / AS was legalised. However, this money was not ring-fenced for palliative care and, after five years, only £184 million could be shown to have been allocated to palliative care.

- In 2022, New South Wales committed to spend an extra $743 million on palliative care over five years when AD / AS was legalised. However, in 2023 this decision was revisited and the palliative care budget was cut by $249 million in one year, resulting in cuts to palliative care staff and services. At the same time, New South Wales allocated $97.4 million in new funding over 4 years to rolling out its AD / AS programme.

- A common problem in different jurisdictions is that, where AD / AS is seen as part of ‘end-of-life’ care then AD / AS competes with palliative care for the same funding pot. Resources for palliative care are thus redirected to fund AD / AS.

vi. The Committee noted that a review from 2020 found ‘very little research on the impact of assisted dying on palliative care once legislation is introduced’. However, more evidence from qualitative studies carried out since this review needs to be considered:

- One study found that ‘Across all three jurisdictions [Flanders, Oregon, Quebec], interviewees expressed some ambivalence about how the practice of assisted dying interacts with palliative care delivery. This appeared most divisive and contested in Quebec.

- Multiple studies found AD / AS associated with ‘significant moral distress and ill-being outcomes’ for healthcare professionals. This was heightened by ‘coercing provider participation’ of individuals and of organisations. This has led to medical professionals leaving their jobs. In Canada, at least one hospice has been forced to close rather than deliver AD / AS. The fears expressed by hospices and palliative care associations seem fully justified.

- Another study found that ‘All participants spoke about the conflict between maintaining Medical Assistance in Dying eligibility and effective symptom control’. This issue was identified in two other studies looking at different jurisdictions. It may explain why in Oregon, Washington and Canada, increasing rates of AD / AS are linked with an increasing proportion citing pain or fear of pain as a reason for seeking death.

vii. The evidence examined here shows clear indications in several jurisdictions of palliative and end-of-life care deteriorating in quality and provision following the introduction of AD / AS, and a negative impact on some healthcare professionals. Recent evidence shows that palliative care is not improving as quickly in jurisdictions with AD / AS as it is in jurisdictions without AD / AS.

viii. The adverse impact of AD / AS on palliative care that has been identified here could perhaps be mitigated, and the evidence shows that the relationship between AD / AS and palliative care develops differently in different jurisdictions. However, the current challenges facing the National Health Service would make it harder to mitigate potentially adverse impacts on funding, staff morale, and trust.

0.0 The House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee Report on Assisted Dying / Assisted Suicide (henceforth ‘the Committee’ and ‘the Report’) [1] did not make recommendations in relation to whether or not some form of physician-assisted suicide or voluntary euthanasia (which the Report termed ‘Assisted Dying / Assisted Suicide’ or ‘AD / AS’) should be legalised.

0.1 The recommendations of the Committee were principally directed to urging the Government to ‘ensure universal coverage of palliative and end of life services, including hospice care at home’. [2] The Committee decided not to ‘call on Government to commission a review of the impact of the existing legislation [on AD / AS]’. [3] The only recommendation in relation to AD / AS was for the UK Government to ‘consider how to respond to another jurisdiction in the UK, or the Crown Dependencies, legislating to allow AD / AS’. [4]

0.2 Rather than seeking to make prescriptions in relation to legalisation, the Committee saw its role as providing evidence to inform any future Parliamentary debate:

Our aim for this report is for it to serve as a basis for discussion and debate in future Parliaments. We have therefore endeavoured to bring together a comprehensive and up-to-date body of evidence relating to this difficult, sensitive, and yet, crucial subject. The debate on AD / AS is not new, and our report is not intended to provide a resolution to it, but we do hope that it will be a significant and useful resource for future Parliamentarians. [5]

0.3 The Committee considered and presented helpful evidence on a range of aspects of AD / AS, but perhaps the most quoted sentence of the Report was its summary of evidence on the impact of AD/AS on palliative care:

In the evidence we received we did not see any indications of palliative and end-of-life care deteriorating in quality or provision following the introduction of AD/AS; indeed the introduction of AD/AS has been linked with an improvement in palliative care in several jurisdictions. [6]

0.4 This sentence, while it occurs at the end of the section ‘Reflections on AD/AS practice in international jurisdictions’ [7] summarises evidence set out in a subsequent section on ‘International evidence on AD/AS and the impact on PEoLC [Palliative and End of Life Care]’. [8] This paragraph, while it may represent the evidence that was put before the Committee is problematic in at least four ways: that some evidence was not relevant to the question, that some was relevant but outdated, that some was speculative, and that a wider range of more recent evidence needs to be considered. [9]

0.5 This evidence cited in the Report can be considered under five headings:

- AD/AS recipients receiving palliative care services;

- Spending on palliative care services after AD/AS legalisation;

- Provision of palliative care services after AD/AS legalisation;

- Impact of AD/AS on palliative care professionals;

- Impact of AD/AS on quality of palliative care.

These will be set out and analysed in turn.

Evidence in the Report

1.0 The Report lists figures for the percentage of those ‘enrolled in’ palliative care services in Oregon (91.4%), Washington (91%), California (95.4%), Colorado (80.2%) and Hawaii (58%) [10] or ‘accessing’ palliative care in New Zealand (76%), Victoria (81%) and Western Australia (85.3%). [11] In Canada, 80.7% of AD/AS recipients had received palliative care and ‘[m]ost people who went through AD/AS (52.6%) received palliative care services for a month or more.’ [12]

Analysis

1.1 In the first place it is inaccurate to say that ‘most people’ in Canada who went through AD/AS received palliative care for a month or more. The figure of 52.6% is the percentage of those AD/AS recipients who received palliative care, not of all AD/AS recipients. The percentage of those who went through AD/AS who received palliative care for more than a month was 42.5%. [13] More recent Canadian data (from 2022) gives the percentage of AD/AS recipients who had received palliative care services for more than a month as only 38.7%. [14] Furthermore, as the Report acknowledges, none of the data from these jurisdictions offers insights into ‘the adequacy or quality of the palliative care services that were available or provided.’ [15]

Conclusion

1.2 These data only show that where AD/AS is legal, AD/AS and palliative care services co-exist. This does not show whether AD/AS has had a positive or negative impact on delivery of palliative care to AD/AS recipients or on other end of life patients. These data are not relevant to understanding the impact of AD/AS on palliative care.

Evidence in the Report

2.0 The Report cites several examples of increases in funding for palliative care after the introduction of AD/AS: ‘in Belgium, Government investment in PEoLC doubled between 2002, when AD/AS was legalised, and 2011’ [16]; ‘Canadian Federal Government’s commitment to invest $6 billion in palliative and home care over 10 years’ [17]; ‘Queensland committed “record investment” in PEoLC services and developed and implemented a new PEoLC strategy prior to legalising AD/AS’ [18]; ‘increased PEoLC spending commitments in the Australian state of New South Wales’ [19]; ‘New South Wales and Victoria also increased investment in PEoLC alongside legalising AD/AS’. [20]

Analysis

2.1 The Belgian data shows that it is certainly possible for funding of palliative care to increase after legalisation of AD/AS. [21] However, these data cover only one country and less than ten years and are from more than ten years ago. It is not clear that this investment has been sustained. Evidence considered in the next section (on provision of palliative care services) would suggest not.

2.2 All the other examples cited in the Report are not of money spent but of a ‘commitment’ to spend money. Such commitments often deliver much less funding in practice. The figure of $6 billion over ten years in Canada, for example, was to be shared between palliative care and home care with no ring-fencing of palliative care. [22] A subsequent audit showed that only $184 million of spending on palliative care could be identified over five years (on average 16.2% of the funding received by these provinces), with no information about how the money had been spent in the most populous provinces. [23]

2.3 In Queensland, Australia, in 2021 the Government committed to spend an extra $171 million towards palliative care over 6 years (i.e. $28.5 million a year). [24] This was only approximately 10% of the increase in funding that Palliative Care Queensland and the Australian Medical Association Queensland had argued was needed. [25] As in Canada, the allocation of this extra funding was opaque. In April 2024, AMAQ urged ‘an independent review into the use of $171 million promised to palliative care in the 2022-23 budget that, so far, remains unaccounted for’. [26]

2.4 In June 2022 the New South Wales Government announced an increase in palliative care spending of $743 million over five years. [27] However, in October 2023 it was revealed that this uplift was being cut by $150 million. [28] In budget hearings in March 2024 it was further stated that that the 2023-2024 budget for palliative care had in fact been cut by $249 million. [29] In practice this has led to cuts in palliative care services in New South Wales of more than 30% in most areas [30], with a direct impact on staffing. [31]

Funds diverted to AD/AS

2.5 While the NSW palliative care budget was effectively being cut, the NSW Government allocated $97.4 million in new funding over 4 years ‘to enable safe and equitable access to voluntary assisted dying [VAD] for eligible people in New South Wales’. [32] Similarly, Victoria budgeted $5.8 million for 2022-2023 towards VAD and a further $23 million for 2023-2024. [33] Queensland, in 2022, set aside $9.3 million over 2 years, mainly to support information and communication technology for AD/AS. [34] It subsequently budgeted funding of a further $18 million over 4 years. [35] This is money that could otherwise have been spent on palliative care services.

2.6 Despite this overt funding for AD/AS, those delivering AD/AS in Australia and Canada frequently complain that AD/AS delivery is under-resourced and / or poorly remunerated [36] with the result that funding or resources have to be diverted from other services to make up the difference, including from palliative care. This phenomenon is shown in qualitative research from Canada.

… when a patient is requesting MAID [Medical Assistance in Dying], most of the resources have been sucked up by that one case and it’s all everyone’s talking about and they’re rushing to get stuff done… everyone from admin down to the bedside nurse is focusing on MAID. And all of the high-quality palliative care that we do falls by the wayside for the other patients. [37]

2.7 Another paper on Canada gave the following examples:

In Ontario, some palliative care nurses are tasked with administration and coordination of MAiD which has been taking up an increasing proportion of their roles—to the point that nurses have left their jobs because they were not able to provide palliative care. In Alberta, British Columbia and Ontario, some Hospice Palliative Care Nurse Practitioners and physicians use their time in paid palliative care roles to provide MAiD, at the direction of health system administrators.

In Ontario, palliative care billing codes are used by doctors to capture and bill for their MAiD work at the direction of the Ministry of Health, despite strong advocacy against this from palliative care medical associations. [38]

2.8 If AD/AS is understood as ‘end-of-life care’, in continuity with conventional palliative care, then both will come under a single budget for which they will then have to compete. Hence Marilyn Gladu MP, who had championed the cause of increasing provision of palliative care in Canada, lamented that, for funding purposes, palliative care in Canada was now being ‘bucketed together with MAID, which was never the intent.’ [39]

2.9 A theme in feedback from providers of AD/AS is that it is under-resourced because the Government had underestimated demand. For example in Victoria:

The implementation of the VAD Act requires significant resourcing including time, money, institutional supports, and peer networks. Yet these supports are not readily available to participants who provide VAD, so they must make do with the resources they can corral from other areas of medical practice. Participants report that coordinating a VAD application through to the patient’s death equates to about sixty hours of working time. [40]

2.10 In Victoria over four years, annual VAD deaths rose from 129 to 306. [41] In Queensland in the first six months there were 245 deaths and in the next 12 months there were 793 deaths – with roughly twice this number initially entering the VAD system. [42] In Canada over seven years the number of assisted deaths rose from 1,018 to 13,241 [43], and there is no sign of this slowing. For comparison Queensland is roughly one tenth of the population of England and Wales, and Canada is roughly half. If take up were similar in England and Wales this would involve hundreds of thousands of hours of staff time, in addition to resources for training, IT support, drugs, management and oversight of the ‘assisted dying’ service. If spending were equivalent to Queensland (where providers complain it is inadequate) this would be more than £100 million in the first year alone with further year on year increases.

2.11 It may well be that ending lives prematurely by AD/AS reduces costs to health and social care spending [44], both public and private. However, these savings would not be seen directly by palliative care. In contrast, palliative care would likely have increased costs and would also be in direct competition with AD/AS for ‘end-of-life’ resources. Such competition for resources would be ongoing and structural, as is seen in various jurisdictions.

Conclusion

2.12 There is evidence that the debate over changing the law on AD/AS can be the occasion for increasing palliative care funding, as for example happened in Belgium. However, there is no evidence that increases in funding after a change in the law have been sustained in the longer term. Moreover, citations of ‘commitments’ to future spending have often been more modest than they initially appear, and less than what is needed to ensure adequate provision of palliative care. In at least one case (New South Wales) a change in the law has been followed by cuts to the budget for palliative care. The costs of delivering AD/AS is often underestimated and these ongoing costs divert money budgeted for ‘end-of-life’ care away from palliative care. By contrast, it is clearly possible for Government to increase funding without simultaneously legalising AD/AS.

Evidence in the Report

3.0 The Report heard evidence from Jan Bernheim that, ‘The hypothesis that legal regulation of physician-assisted dying slows development of PC [Palliative Care] is not supported by the Benelux [Belgium / Netherlands / Luxembourg] experience…’ [45]

3.1 Similarly evidence was heard from Canada that ‘the use of palliative care has risen by almost 10% across the board of the population, which is almost certainly the fastest rate of growth of palliative care in Canadian history.’ [46]

3.2 The Report also cites an Australian report from 2018 which showed that ‘in the USA, the provision of PEoLC in states that had legalised AD/AS was higher than the national average. For example, in 2015, 93% of hospitals in Washington State and 89% in Oregon had a PEoLC team, compared to 77% in the wider Pacific Coast region and 67% nationally.’ [47] The Report updates these figures with American data from 2019, which show that ‘six of the seven US states which had legalised AD/AS by 2019 had higher provision of PEoLC in hospitals than the national average.’ [48]

Analysis

3.3 A journal article already cited shows increases in funding of palliative care in Belgium after the passing of the Euthanasia Act of 2002 until 2011. However, in the article it is stated that, ‘Continued monitoring of both permissive and non-permissive countries, preferably also including indicators of quantity and quality of delivered care, is needed to evaluate longer-term effect.’ [49]

3.4 It is easier to measure quantity than quality of provision (quality will be discussed below). An important study from 2020 compares provision of three different forms of palliative care service (home care teams, inpatient palliative care services, and hospital support teams) in 51 European countries across 14 years. The study found that all of these services had increased over time, but with a slightly different pattern in Western Europe from Central and Eastern Europe. [50] The study did not analyse differences between AD/AS and non-AD/AS countries, but the data can be used to make this comparison.

3.5 Taking the three services together, Belgium showed a marked growth in number of palliative care services between 2005 and 2012 (of more than 50%). [51] This reflects what was known from earlier research. [52] However, between 2012 and 2019 the number of palliative care services in Belgium declined. [53] Furthermore, taking the four European countries with AD/AS (Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Switzerland) and comparing these with twenty non-AD/AS countries in Western Europe, the increase in palliative care provision in non-AD/AS countries between 2012 and 2019 was higher in all three categories. Overall provision in non-AD/AS countries grew by 25% whereas in AD/AS countries it grew by 7.9%. [54] Interestingly, this increase among AD/AS countries was primarily because of Switzerland which has a model of AD/AS provision that stands outside mainstream healthcare. In the Benelux countries between 2012 and 2019 the numbers of palliative care services declined by 4.7%. [55]

3.6 In Canada, the increase in funding for palliative care was not directly due to the legalisation of MAiD but was a response to a Private Members Bill devoted to palliative care which was sponsored by Conservative MP Marilyn Gladu. [56] This was introduced to mitigate the dangers of MAiD legislation but clearly could have been introduced independently of MAiD legislation. The need for an increase in palliative care provision was very evident. In 2017, only a third of Canadians had access to palliative care, often for just a short time before death. The Canadian Society of Palliative Care Physicians estimated that Canada needed to double the number of palliative care physicians in order to ensure adequate palliative care cover. [57] Thus the increases noted by the Report were from a very low base. Furthermore, as noted above, Marilyn Gladu has expressed frustration that most of the money promised has not been spent on palliative care and that some money has been siphoned off to fund AD/AD services. [58] It remains to be seen whether the current increases in provision in Canada will be sustained.

3.7 The third area considered by the Committee was the United States, with the Report noting that, in 2015, a higher proportion of hospitals in Washington State and in Oregon had a palliative care team than the regional or national average. [59] Furthermore, more recent data showed that six of the seven U.S. States / jurisdictions which had legalised AD/AS by 2019 had higher provision than the national average. However, all seven of these jurisdictions had higher than average palliative care provision before they adopted AD/AS. [60] Furthermore, while Oregon and Washington initially saw higher than average growth (between 2008 and 2011), between 2015 and 2019 Oregon has remained the same and Washington has declined. [61]

3.8 Indeed taking these seven as a group, three of which legalised AD/AS between 2015 and 2019, over this period they had lower growth in palliative provision than non-AD/AS states, whether on the measure of the number of hospital palliative care teams or the proportion of hospitals with palliative care teams. The AD/AS states saw an increase of 3.2% in the number of teams (from 276 to 285) and an increase of 0.8 percentage points in the proportion of hospitals with a palliative care team (from 78.4% to 79.2%). The non-AD/AS states saw an increase of 9.4% in number of teams (from 1,315 to 1,438) and an increase of 5.8 percentage points in proportion of hospitals with palliative care teams (from 64.4% to 70.2%).

3.9 The most recent data thus shows that both in Western Europe (4 countries out of 24) and in the United States (7 states / jurisdictions out of 51), provision of palliative care services has increased more in jurisdictions without AD/AS than in jurisdictions with AD/AS.

Conclusion

3.10 Jurisdictions with AD/AS have seen increases in provision of palliative care in the past. However, the most recent data, both from Western Europe and from the United States, shows that, on average, jurisdictions without AD/AS have had larger increases in provisions in palliative care than those with AD/AS.

Evidence

4.0 The Report noted that a systematic scoping study by Gerson et al. had found that, whereas palliative care and AD/AS in Belgium were parts of ‘an integrated practice’ [62], other than in Belgium, ‘the introduction of AD/AS was met with resistance from many medical and palliative care associations’. [63] However, the same study found ‘very little research on the impact of assisted dying on palliative care once legislation is introduced.’ [64]

Analysis

4.1 Gerson notes the sparsity of evidence for the impact of AD/AS on palliative care. However, the paper did identify some evidence and the major conclusion was that the relationship between palliative care and AD/AS was highly variable: ‘We categorize the relationship in the four countries where there was relevant literature [Belgium, Switzerland, Canada and the United States] as variously: supportive, neutral, coexisting, not mutually exclusive, integrated, synergistic, cooperative, collaborative, opposed, ambivalent, and conflicted.’ [65]

4.2 One element of conflict related to institutional policies. Gerson highlighted instances of professionals who wished to deliver or accompany people through AD/AS while the hospice had a policy prohibiting such practices. [66]

4.3 Subsequent to Gerson’s literature review there have been a number of new studies published, including one by Gerson examining differences of approach in Flanders, Quebec and Oregon. In that study it was found that ‘Across all three jurisdictions, interviewees expressed some ambivalence about how the practice of assisted dying interacts with palliative care delivery. This appeared most divisive and contested in Quebec’. [67]

4.4 This qualitative survey was also useful in highlighting problems connected to the Belgium model. In the literature review, for which two out of four papers on Belgium were by Jan Bernheim [68], the model in Belgium was described as an ideal or ‘prototype’ [69] for a synergetic relationship between palliative care and AD/AS. However, the qualitative interviews demonstrate ambivalence about the direction of AD/AS provision in Belgium, which is increasingly for non-terminal conditions, and that this shift was increasing tension between AD/AS and palliative care.

4.5 Another theme that was echoed in all three jurisdictions was that AD/AS received undue media attention and that palliative care was misunderstood by the public.

Some interviewees [in Flanders] argued that euthanasia receives a lot of public and media attention whereas palliative care does not. Consequently, they feared people might request euthanasia without being aware of palliative care options. [70]

Others [in Oregon] expressed concern that palliative care was not given as much public attention as assisted dying, which distorted the reality on the ground in terms of the numbers opting for assisted dying versus those in receipt of palliative care: [71]

Interviewees in Quebec reported that the public’s lack of knowledge about and access to palliative care services is a great problem, which affects the relationship with assisted dying. Interviewees recounted instances of patients and families requesting MAiD because of insufficient symptom relief and care. [72]

4.6 Sometimes the provision of both AD/AS and palliative care reinforces a public misperception that palliative care involves the intentional ending of life:

Because already there is an attitude among many of our clients that ‘if I go into hospice, they’re going to kill me because that’s what a hospice does’. [73]

4.7 This case is from Oregon but a similar misperception was reported in a different study from Canada.

There was one family who was very concerned that we were also the MAID team… they had a huge fear of what was palliative care and that we were somehow going to do something to facilitate his death. [74]

4.8 Again, a recent study from Australia, shows that this is impacting palliative care professionals:

It’s affecting us in palliative medicine, more than we would like and more than it should because of the assumption that because we specialise in end-of-life care therefore, this is for us. And so, the general perception amongst medical practitioners, the health community and the general public is that this is our thing. And so, for a lot of us, we’re saying, no, this is not our thing. [75]

4.9 A number of studies have found evidence of the implementation of AD/AS being associated with ‘significant moral distress and ill-being outcomes’ [76] among healthcare professionals, ‘moral distress may arise from pressure experienced during decision-making and service provision from practitioners’ colleagues, or from family members of the patient.’ [77] In law there are typically provisions for conscientious objection from having to be involved in providing AD/AS but in practice these afford limited protection, especially in the case of junior doctors working with senior colleagues who provide AD/AS. [78]

4.10 It is in this context that it has been stated that after the introduction of AD/AS, some are leaving palliative medicine:

Some interviewees [in Quebec] strongly believed that assisted dying was eroding palliative care through a siphoning of funds, associated cultural changes, and a devaluation of palliative care professionals who, it was suggested, were increasingly leaving the field. [79]

4.11 This echoes what was stated earlier about nurses [in Ontario] who ‘have left their jobs because they were not able to provide palliative care’. [80]

4.12 An area of conflict identified by Gerson, and by others, is whether hospices are able to provide a safe environment where AD/AS is not offered, or whether they are forced to deliver AD/AS alongside conventional palliative care. If hospices are permitted to have policies that exclude AD/AS this can help retain staff and reassure some patients, but some members of staff and some patients may perceive it as a ‘barrier to access’. [81] This way of framing the issue can lead to ‘coercing provider participation’ [82] In AD/AS. In Canada at least one hospice has been forced to close rather than deliver AD/AS. [83]

Conclusion

4.13 The model of ‘integrated’ AD/AS and palliative care in Belgium, where palliative care professionals are significantly involved in delivering AD/AS, is unique to that jurisdiction. It cannot simply be transplanted to other countries with a different history, culture and workforce. Furthermore, the Belgian model is intertwined with a practice of AD/AS which is no longer restricted to the context of terminal illness, and this is bringing its own tensions as it get further and further from palliative care as traditionally understood.

4.14 Outside Belgium, there is mounting evidence from multiple studies of the potential of AD/AS to lead to palliative care professionals experiencing demoralisation, moral distress and even leaving the profession because they are no longer able to deliver palliative care without being pressurised into facilitating AD/AS. The fears of hospices [84] and palliative care associations in the United Kingdom and in most jurisdictions worldwide are fully justified. Palliative care in the United Kingdom is currently world-leading. Legalisation of AD/AS threatens the professionals and organisations that deliver this outstanding level of care and jeopardises what has been an international beacon of excellence.

Evidence

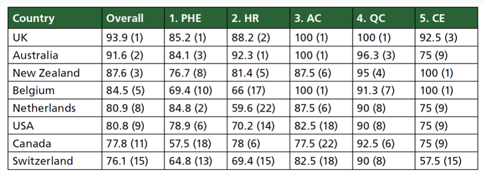

5.0 The Report states that the Committee ‘did not see any indications of palliative and end-of-life care deteriorating in quality or provision following the introduction of AD/AS’. [85] However, there is no presentation of evidence in the Report in relation to the ‘quality’ of palliative care in jurisdictions with AD/AS, other than a table reproduced at the end of the discussion of Quality of palliative and end of life care in the UK. [86]

5.1 The jurisdictions listed, other than the United Kingdom, have all introduced some form of AD/AS and hence are discussed in the Report. However, it should be noticed that the data in the table is from 2015, and this before AD/AS had been introduced in Australia, New Zealand and Canada and when it was confined to only 4 states in the USA. This table shows that those countries with AD/AS, that is Belgium, the Netherlands, Switzerland and (parts of) USA, were in the top quartile of 80 countries, albeit below the UK, Australia and New Zealand.

Analysis

5.2 A similar study of quality of death was published in 2010 [87], though it only considered 40 countries. In 2022 a new study was published on quality of death and dying, this time looking at 81 countries. [88] These studies do not use identical methodologies nor the same scoring systems but they are analogous in that they look at more than one dimension of quality and seek an overall ranking between countries.

5.3 There is very little change between 2010 and 2015, either in ranking within this cohort or ranking in relation to the longer list of countries. However, between 2015 and 2022 most countries with AD/AS have fallen in ranking in relation to the longer list of countries, with Canada, Belgium and the United States dropping out of the top quartile.

5.4 The exception to this pattern is Switzerland which, as noted above, has a model of AD/AS provision that stands outside mainstream healthcare, and thus outside palliative care. The pattern in this change of rank in quality of death is congruent with the 2020 study of level of palliative care provision in 51 European countries [89], and with data on provision of palliative care in the USA over time. [90] Together they suggest that since 2015 jurisdictions with AD/AS have lost ground to non-AD/AS countries both in quantity and in quality of palliative and end-of-life care.

Qualitative studies

5.5 Assessment of quality of palliative care requires qualitative research. As mentioned above, and noted in the Report, there is an urgent need for further research in this area. In addition to other new studies mentioned in the present paper thus far [91], all of which were published after the systematic scoping review cited the Report [92], an important paper was published in 2024 after the Report itself had been produced. This directly considered the question: ‘Does voluntary assisted dying impact quality palliative care?’ [93] It was a retrospective mixed-method study drawing on data from Victoria, Australia.

5.6 The conclusion of this study was that the possibility of AD/AS ‘impacted multiple quality domains, both enhancing or impeding whole person care, family caregiving and the palliative care team’. [94]

5.7 The principle enhancement is that where a patient raised the issue of AD/AS this could be an occasion for improved communication. This study, as with other studies, has highlighted that ‘when a request for VAD was appropriately explored by seeking to understand the motivation for a hastened death, patients were more open to considering therapeutic options’. [95]

5.8 The principle impeding factor is also communication. Where there are differences of views within families [96] this can lead to lack of openness among families and carers, for example, a husband is described as ‘struggling with wife’s decision’, while a father withheld information from his family, citing concerns that ‘his youngest son would have problems with VAD’. [97]

5.9 Similarly, among professionals, some were concerned that ‘VAD enquiries sometimes detracted from usual discussions of optimising symptoms and quality of life.’ [98] From a patient perspective, because AD/AS presents itself as the solution to issues that cannot be addressed by palliative means, a focus on AD/AS can lead to disengagement from palliative care and symptom relief.

Patients withheld information on VAD on account of ‘not wanting to offend anyone’s values’. Fear of judgement motivated secrecy, isolating patients, caregivers and staff, with families not wanting palliative care to ‘know the full story’ and ‘declining extra hours of home support’. On occasion, services were only aware of access to VAD following the death of a patient. [99]

Staff moral distress and ambivalence: Staff struggled with the patients and families on occasion distancing themselves from palliative care services, refusing visits or ‘not ‘want(ing) to talk in detail about (her) pain management’ or ‘alternatives to VAD’ as the focus was how ‘she could access VAD’. [100]

5.10 In one instance the study noted a patient ‘did not want morphine increased, as he wanted to remain alert (for VAD)’. [101] This same concern was expressed in a different study in Canada:

All participants spoke about the conflict between maintaining Medical Assistance in Dying eligibility and effective symptom control. One of the ways this conflict manifested was in withholding symptom control medications that could cause sedation or confusion and could jeopardize eligibility, as patients needed to be capable of consent at the time Medical Assistance in Dying is delivered.’ [102]

5.11 Again, in another Canadian study:

Indeed, the initiation of the MAiD process in actively dying patients may compromise symptom management, since patients may refuse opioids in order to retain capacity for consent; [103]

5.12 It should be noted that this phenomenon, of reduced symptom control, either due to lack of communication or partial disengagement from palliative care services or from the perceived requirements of the AD/AS process, would not be captured in data about whether the patient was ‘enrolled’ with a hospice or ‘receiving’ palliative care. How then can we assess the apparent adverse effect on symptom relief in more quantitative terms?

Concern about pain

5.13 For many people, first among the criteria for a good death is the absence of, or at least the amelioration of physical pain. [104] Pain relief is a key objective for effective palliative care and addressing unmet need for pain relief at the end of life has often been cited as a reason for legalising AD/AS. However, data from multiple jurisdictions with AD/AS shows that the primary motivation for seeking assisted death is existential problems rather than physical, and concerns autonomy, loss of enjoyment in life, and perceived lack of dignity and fears about being a burden on others. [105] ‘Pain or fear of pain’ only appears further down the list.

5.14 It can nevertheless be asked whether, as AD/AS becomes more well-established, concerns about pain have become more or less common. A study of reasons for seeking euthanasia in the Netherlands between 1977 and 2001 found that the ‘importance of pain in such requests decreased significantly’. This change was attributed to ‘improvements in pain management’. [106] However, a second study found ‘no significant differences between the 5-year period before and after implementation of the Euthanasia Act’ in 2002. [107] There was no improvement, but at least there was no deterioration.

5.15 There is some evidence that shortly after the law in Oregon was passed – that is, between 1997 and 2002 – concerns about pain relief increased in Oregon. [108] This is seen in reports by relatives. However, it is far from clear that this deterioration was due to the passing of the law. A more widely accepted explanation is that the attempt by the Attorney General, John Ashcroft, to oppose the Oregon law at a federal level led to a reluctance on the part of healthcare professionals to prescribe pain relief, lest they be liable for hastening death. [109]

5.16 Examination of the data over a longer period, however, shows that concern about pain has risen significantly in Oregon, reported as a concern in 6.7% of those receiving AD/AS in the first report for 1998 [110], to 34.3% in the most recent report for 2023. [111] A similar pattern is found in Washington which saw an increase from 25% in 2009, to 46% in 2022. [113] Canada has only four reports so far, but it too has seen an increase in concern about pain from 53.9% in 2019 [114], to 59.2% in 2022. [115] These increases cannot be attributed to Ashcroft’s attempts to overturn the law in Oregon, which were resolved in 2005. They seem to have occurred consistently across more than two decades and in three different jurisdictions. They point to an association, for whatever reason, between increased provision of AD/AS and increase in experience of or fear of pain as a reason for having AD/AS.

Conclusion

5.17 Measuring quality of provision of palliative care is more difficult than measuring quantity of provision, and more research is needed on the impact of AD/AS on the quality of palliative care.

5.18 It can, nevertheless, be said that a recent study on the quality of death and dying is congruent with the most recent studies on the quantity of provision. These point to jurisdictions with AD/AS failing to match levels of improvement in palliative care in countries without AD/AS.

5.19 Qualitative research points to risks and opportunities in the implementation of AD/AS. Discussion of AD/AS can be an occasion for enhanced communication but there is clear evidence, from multiple studies in different jurisdictions that implementing AD/AS can have an adverse impact on symptom control. These findings are seemingly confirmed by quantitative data from 26 years in Oregon, 14 years in Washington and 4 years in Canada. Over time pain or fear of pain has not decreased but has increased as an end-of-life concern in those receiving AD/AS in jurisdictions with AD/AS.

6.1 On the basis of the evidence before it, the Committee considered that:

In the evidence we received we did not see any indications of palliative and end-of-life care deteriorating in quality or provision following the introduction of AD/AS; indeed the introduction of AD/AS has been linked with an improvement in palliative care in several jurisdictions.

6.2 A more complete review of the available evidence points in the opposite direction.

The evidence examined here shows clear indications in several jurisdictions of palliative and end-of-life care deteriorating in quality and provision following the introduction of AD/AS, and a negative impact on some healthcare professionals. Recent evidence shows that palliative care is not improving as quickly in jurisdictions with AD/AS as it is in jurisdictions without AD/AS.

If the issues discussed here affect you or someone close to you, you can call Samaritans on 116 123 (UK and ROI), visit their website https://www.samaritans.org/ or contact them on jo@samaritans.org.

If you are reporting or writing about a case of death by suicide, whether assisted or non-assisted, please consult media guidelines https://www.samaritans.org/about-samaritans/media-guidelines/ on how to do so responsibly.

[1] House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee, Report on Assisted Dying / Assisted Suicide, Second Report of Session 2023–24 HC 321, 29 February 2024.

[2] Ibid., page 88, para. 278; page 97, para. 13.

[3] Ibid., page 118.

[4] Ibid., page 23, para. 68; page 95, para. 6.

[5] Ibid., page 5, para. 11; page 95, para. 1.

[6] Ibid., page 53, para. 142; page 96, para. 7.

[7] Ibid., pages 44-53, paras 115-144.

[8] Ibid., pages 73-77, para. 219-234.

[9] With gratitude to Dominic Whitehouse and all who have drawn my attention to new research and / or made comments on earlier drafts of this paper. Any weaknesses that remain are my own.

[10] Ibid., page 74, para. 221.

[11] Ibid., page 74, para. 222.

[12] Ibid., pages 73-73, para. 220.

[13] That is, 4,225 out of 9,950. See Third Annual Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada (2021), Table 4.4: MAID Recipients Who Received Palliative Care and Disability Support Services, 2021.

[14] That is, 5,071 out of 13,102. See Fourth Annual Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada (2022), Table 4.4: MAID Recipients Who Received Palliative Care and Disability Support Services, 2022.

[15] Op. cit., Third Annual Report on MAiD in Canada (2021), section 4.4, quoted by the Report page 75, para. 227.

[16] Op. cit., the Report (2024), page 77, para. 234.

[17] Ibid., page 77, para. 232.

[18] Ibid., page 77, para. 233.

[19] Ibid., page 75, para. 225.

[20] Ibid., page 77, para. 233.

[21] Chambaere K, Bernheim Jl. ‘Does legal physician-assisted dying impede the development of palliative care? The Belgian and Benelux experience’. J Med Ethics 2015. 41(8):657-60.

[22] Health Canada. The Framework on Palliative Care in Canada—Five Years Later: A Report on the State of Palliative Care in Canada (15 December 2023), section 3.

[23] Parliamentary Budget Officer. Federal Investments in Palliative Care (18 December 2020).

[24] Queensland Government. State Parliament lights up for Palliative Care Week (24 May 2021).

[25] Palliative Care Queensland. Letter to Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk MP (14 September 2021).

[26] AMA Queensland Media Release. Review of end-of-life funding needed (13 May 2024).

[27] Australian Associated Press. ‘Dominic Perrottet says NSW palliative care boost will rectify his past mistakes’, Guardian (9 June 2022), cited by Written evidence to the Committee submitted by Sue Ryder (ADY0256).

[28] Palliative Care NSW News. Palliative Care funding attracting important attention (17 October 2023).

[29] AMA NSW Media. Inadequate Health Budget Impacts Those Most in Need (1 March 2024).

[30] Australian Associated Press. Most regional areas hit with 30pct palliative care cut (22 February 2024).

[31] ‘In Budget Estimates, the Minister admitted that the number of full-time positions for our region [Illawarra] has been reduced from 15 full time positions to less than 10’, Graham Ward MP (11 April 2024).

[32] ‘49: How much money is being spent on enabling access to VAD in regional and rural NSW?’, Budget Estimates – 26 October 2023, Health, Regional Health & the Illawarra and the South Coast: Responses to Supplementary Questions.

[33] Victorian Parliamentary Budget Office. Lapsing funding initiatives: Programs announced between 2020—21 and 2023—24 (19 April 2024), page 74.

[34] Queensland Budget 2022-23: Budget Measures: Budget Paper No. 4 (30 June 2022), page 122.

[35] Ibid., page 131.

[36] VADANZ News. State of VAD report finds remuneration a priority (5 September 2024).

[37] Mathews JJ, et al. ‘Impact of medical assistance in dying on palliative care: a qualitative study’. Palliative Medicine, 2021. 35(2), 447-454, page 451.

[38] Herx L, Kaya E. ‘Palliative care and medical assistance in dying’. In Kotalik J and Shannon DW (eds). Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) in Canada: Key Multidisciplinary Perspectives, Springer International Publishing, 2023: 195-209, page 202.

[39] Special Joint Committee on Medical Assistance in Dying, Number 004, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, Evidence, Thursday 28 April 2022 (at 19.53).

[40] Rutherford J, Willmott L, & White BP. ‘What the doctor would prescribe: physician experiences of providing voluntary assisted dying in Australia’. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 2023. 87(4): 1063-1087, page 1070.

[41] Victoria VAD Review Board. Annual Report July 2022 to June 2023, page 5.

[42] Queensland VAD Review Board. 2023–2024 Annual Report, page 10.

[43] Op. cit., Fourth Annual Report on MAiD in Canada (2022), Chart 3.1: Total MAID Deaths in Canada, 2016 to 2022.

[44] See Parliamentary Budget Officer (Canada). Cost Estimate For Bill C-7 ‘Medical Assistance In Dying’ (20 October 2020); Shaw D and Morton A. ‘Counting the cost of denying assisted dying’. Clinical Ethics. 2020;15(2):65-70. doi:10.1177/1477750920907996. Both of these focus on healthcare costs and overlook potentially much larger savings in terms of social and nursing care, welfare, pensions and general living costs, though these savings would be to pension funds, financial heirs and other government departments rather than to health services.

[45] Op. cit., the Report, page 65, para. 226, citing Written evidence to the Committee submitted by Professor Jan Bernheim (ADY0334) who in turn is citing op. cit., Chambaere and Bernheim, J Med Ethics 41(8):657-60, 2015.

[46] Ibid., page 75, para. 228, citing oral evidence form Professor James Downar (Q 178), no further references provided.

[47] Ibid., page 77, para. 234, citing an Australian report entitled, ‘Experience internationally of the legalisation of assisted dying on the palliative care sector’ (28 October 2018). The footnote gives the author as ‘Palliative Care Australia’, but this is misleading and PCA is the commissioning body rather than the author. The body that produced the report is the private consultancy ‘Aspex Consultancy’, who do not provide names of authors, editors, contributors and reviewers of their report. For an example of transparency in relation to writing, editing, contributing and reviewing see Gajjar D, Hobbs A. POSTBrief on Assisted Dying (26 September 2022). The evidence in the Aspex report on American states is taken from America’s Care of Serious Illness. A State-By-State Report Card on Access to Palliative Care (2015), Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC).

[48] Ibid., page 77, para. 234, drawing on America’s Care of Serious Illness. A State-By-State Report Card on Access to Palliative Care (2019), Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC).

[49] Op. cit., Chambaere and Bernheim, J Med Ethics 41(8):657-60, 2015.

[50] Arias-Casais N, et al. ‘Trends analysis of specialized palliative care services in 51 countries of the WHO European region in the last 14 years’. Palliative Medicine, 2020. 34(8), 1044-1056.

[51] From 115 services to 175.

[52] Op. cit., Chambaere and Bernheim, J Med Ethics 41(8):657-60, 2015.

[53] From 175 to 174.

[54] From 2760 to 3451 and from 546 to 589 respectively.

[55] From 469 to 447.

[56] Private Member’s Bill C-277, An Act providing for the development of a framework on palliative care in Canada (introduced 30 May 2016, Royal Assent given 12 December 2017).

[57] Vogel L. ‘Canada needs twice as many palliative specialists’. CMAJ 2017 Jan 9;189(1):E34–E35. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-5354.

[58] Op. cit., Evidence to Special Joint Committee on MAiD (2022).

[59] Op. cit., the Report, page 77, para. 234, citing op. cit. Aspex Report 2018 itself based on op. cit. CAPC State-By-State Report Card (2015).

[60] See State-By-State Report Card, CAPC (2008). The one State that had legalised physician-assisted suicide prior to 2008 was Oregon. This state did so in 1997, before the system of palliative care Report Cards. However, Oregon was already taking a national lead in palliative care in 1996 before the law came into force. See Tilden VP et al. ‘Oregon's physician-assisted suicide vote: its effect on palliative care’. Nursing Outlook. 1996. 44(2), 80-83.

[61] Oregon remains on 88.9% (24 out of 27 hospitals) whereas Washington State declined from 92.7% (38 out of 41) to 84% (42 out of 50). All data taken from op. cit., State-By-State Report Cards for 2015 and 2019.

[62] Op. cit., the Report, page 76, para. 230.

[63] Ibid., the Report, page 76, para 230, paraphrasing Gerson SM, et al. ‘Relationship of Palliative Care With Assisted Dying Where Assisted Dying is Lawful: A Systematic Scoping Review of the Literature’, Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 59 (2020): 1287–1303.

[64] Ibid., the Report, page 76, para. 230, directly quoting op. cit., Gerson et al. page 1300.

[65] Op. cit., Gerson et al., page 1287.

[66] Ibid., page 1298.

[67] Gerson SM, et al. ‘Assisted dying and palliative care in three jurisdictions: Flanders, Oregon, and Quebec’. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 2021. 10(3), 3528-3539, page 3536.

[68] Bernheim JL, Distelmans W, Mullie A, & Ashby A. ‘Questions and answers on the Belgian model of integral end-of-life care: Experiment? Prototype?’ J Bioeth Inq 2014;11:507e529 and Bernheim JL, et al. ‘Development of palliative care and legalisation of euthanasia: antagonism or synergy?’. BMJ, 2008. 336(7649), 864-867.

[69] Ibid., Bernheim et al. (Questions and answers on the Belgian model, 2014).

[70] Op. cit., Gerson et al. 2021, page 3533.

[71] Ibid., page 3534.

[72] Ibid., page 3536.

[73] Ibid., page 3534.

[74] Op. cit., Mathews et al. 2021, page 451. On this theme, see also Chochinov HM, Fins JJ. ‘Is Medical Assistance in Dying Part of Palliative Care?’. JAMA, 2024. 332(14), 1137-1138.

[75] Op. cit., Rutherford et al. 2023, page 1069.

[76] Wibisono S, et al. ‘Attitudes toward and experience with assisted-death services and psychological implications for health practitioners: A narrative systematic review’. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/003022282211389 This paper considers 15 qualitative and 3 quantitative studies.

[77] Ibid.

[78] McDougall RJ, White BP, Ko D, Keogh L, & Willmott L. ‘Junior doctors and conscientious objection to voluntary assisted dying: ethical complexity in practice’. Journal of Medical Ethics, 2022. 48(8): 517-521.

[79] Op. cit., Gerson et al. 2021, page 3535.

[80] Herx and Kaya in Kotalik and Shannon (eds) 2023, page 202.

[81] Hamer MK, et al. ‘Conscience-Based Barriers to Medical Aid in Dying: A Survey of Colorado Physicians’. J Gen Intern Med. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08782-y

[82] Carpenter T, & Vivas L. ‘Ethical arguments against coercing provider participation in MAiD (medical assistance in dying) in Ontario, Canada’. BMC Medical Ethics, 2020. 21(1), 46.

[83] ‘Layoff notices issued at B.C. hospice that refused to offer medical assistance in dying’, CBC News (9 January 2021); Flanders N. ‘Canadian health authorities reportedly ‘destroying palliative care’ in favor of assisted suicide’, Live Action (7 August 2023).

[84] It is noticeable that the Kim Leadbeater’s Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill which is due to have its Second Reading on 29 November 2024 both requires professionals to refer patients for AD/AS (section 4(5)), which is contrary to the policy of the BMA and of the WMA, and also has no institutional protection for organisations such as hospices, and indeed seems to prohibit employers (whether NHS, charity, or private) from requiring professionals not to provide, offer, assess or even raise the issue of AD/AS with patients (Section 23(2)).

[85] Op. cit., the Report, page 53, para. 142; page 96, para. 7.

[86] Ibid., page 80, para. 242, Table 9. Data taken from the Economist Intelligence Unit. The Quality of Death Index–Ranking Palliative Care Across the World (October 2015).

[87] The Economist Intelligence Unit. The Quality of Death: Ranking end-of-life care across the world (July 2010).

[88] Finkelstein EA, et al. ‘Cross country comparison of expert assessments of the quality of death and dying 2021’. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 63.4 (2022): e419-e429.

[89] Op. cit., Arias-Casais et al. 2020.

[90] Op. cit., State-By-State Report Card, CAPC 2015; State-By-State Report Card, CAPC 2019.

[91] Op. cit., Carpenter & Vivas 2020; Gerson et al. 2021; Mathews et al. 2021; McDougall et al. 2022; Wibisono et al. 2022; Herx & Kaya 2023; Rutherford et al. 2023; Hamer et al. 2024.

[92] Gerson et al. 2020 (note that while this review appeared in 2020 it was accepted for publication on 13 December 2019).

[93] Michael N, Jones D, Kernick L, & Kissane D. ‘Does voluntary assisted dying impact quality palliative care? A retrospective mixed-method study’. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. 2024;0:1–10. doi:10.1136/spcare-2024-004946.

[94] Ibid., page 1.

[95] Ibid., page 5.

[96] Serota K, Buchman, DZ, & Atkinson M. ‘Mapping MAiD Discordance: A Qualitative Analysis of the Factors Complicating MAiD Bereavement in Canada’. Qualitative Health Research 34.3 (2024): 195-204.

[97] Op. cit., Michael et al. 2024, page 7.

[98] Ibid., page 5.

[99] Ibid., page 7.

[100] Ibid., page 7.

[101] Ibid., page 6, Table 4.

[102] Op. cit., Mathews et al. 2021, page 450.

[103] Li M, et al. ‘Medical assistance in dying—implementing a hospital-based program in Canada’. N Engl J Med, 2017. 376(21), 2082-2088, 2087.

[104] Steinhauser KE, et al. ‘Factors Considered Important at the End of Life by Patients, Family, Physicians, and Other Care Providers’. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2476-82; Zaman M, Espinal-Arango S, Mohapatra A, & Jadad AR. ‘What would it take to die well? A systematic review of systematic reviews on the conditions for a good death?’ Lancet Healthy Longevity (September 2021) 2.9: e593-e600.

[105] Oregon Health Authority Oregon Death with Dignity Act 2023 Data Summary, page 14; Center for Health Statistics (Washington) Report to the Legislature 2022 Death with Dignity, June 2023, page 7; op. cit., Fourth Annual Report on MAiD in Canada (2022) Chart 4.3: Nature of Suffering of Those Who Received MAID, 2022; Voluntary Assisted Dying Board Western Australia. Annual Report 2022–23, page 22.

[106] Marquet RL, Bartelds A, Visser GJ, Spreeuwenberg P, & Peters L. ‘Twenty five years of requests for euthanasia and physician assisted suicide in Dutch general practice: trend analysis’. BMJ, 2003. 327(7408), 201-202, page 202.

[107] van Alphen JE, Donker GA, & Marquet RL. ‘Requests for euthanasia in general practice before and after implementation of the Dutch Euthanasia Act’. British Journal of General Practice, 2010. 60(573), 263-267, page 266.

[108] Tolle SW, Tilden VP, Rosenfeld AG, & Hickman SE. ‘Family Reports of Barriers to Optimal Care of the Dying’. Nursing Research November 2000.49(6):p 310-317; Fromme EK, et al. ‘Increased family reports of pain or distress in dying Oregonians: 1996 to 2002’ Journal of Palliative Medicine 7.3 (2004): 431-442.

[109] This was analogous to the ‘Shipman’ effect in the United Kingdom, where the conviction of a medical serial killer who murdered by use of lethal doses of diamorphine, led doctors to be reluctant to prescribe opioids even for people in great pain. Gao W, Gulliford M, Bennett MI, Murtagh FE, & Higginson IJ. ‘Managing cancer pain at the end of life with multiple strong opioids: a population-based retrospective cohort study in primary care’. PLoS One, 2014. 9(1), e79266.

[110] Oregon Health Division, Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act: The First Year’s Experience (1998), page 16.

[111] Op. cit., Oregon Death with Dignity Act Report 2023 Data Summary, page 14.

[112] Washington State Department of Health 2009 Death with Dignity Act Report, page 7, Table 3.

[113] Op. cit., Washington State Report to the Legislature 2022 Death with Dignity, page 7.

[114] First Annual Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada (2019) Chart 6.1: Nature of Suffering of Those Who Received MAID, 2019.

[115] Op. cit., Fourth Annual Report on MAiD in Canada (2022), Chart 4.3: Nature of Suffering of Those Who Received MAID, 2022.

Most recent

A Human Right to Suicide Prevention: Analysis of ‘The Impact of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill III’

03 June 2025

An Equal Opportunity to Live: Analysis of ‘The Impact of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill II’

03 June 2025

Ending Life as Cutting Costs: Analysis of ‘The Impact of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill I’ (Professor David Albert Jones)

23 May 2025

Sincerest Thanks for Your Support

Staff are grateful to all those who sustained the Centre in the past by their prayers and the generous financial support from trusts, organisations, communities and especially from individual donors, including the core funding that came through the Day for Life fund and so from the generosity of many thousands of parishioners. We would finally like to acknowledge the support the Centre has received from the Catholic community in Ireland, especially during the pandemic when second collections were not possible.

We would like to emphasise that, though the Centre is now closed, these donations have not been wasted but have helped educate and support generations of conscientious healthcare professionals, clerics, and lay people over almost 50 years. This support has also helped prevent repeated attempts to legalise euthanasia or assisted suicide in Britain and Ireland from 1993 till the end of the Centre’s work on 31 July 2025.