Bioethics in Brief: Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide

Bioethics In Brief – Euthanasia And Assisted SuicideEuthanasia and assisted suicide both refer to the intentional ending of a patient’s life, typically at their request, where death is thought to be of benefit to the patient. The difference lies in who carries out the life-ending act. In the case of euthanasia, the lethal dose is administered by someone else, typically a doctor. With assisted suicide, as the word ‘suicide’ suggests, the patient requesting it administers the dose themselves, although the means of death are provided by someone else (hence why it is ‘assisted’).

Euthanasia is associated with what is generally practised in the Low Countries: Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, and also in Canada. Assisted suicide is practised in Switzerland and some US states such as Oregon and California.

Some favour assisted suicide over euthanasia in part because assisted suicide is seen as enhancing choice and control for the patient, and so seems less open to abuse, given that the consenting patient must ultimately perform the life-ending act on themselves. It seems, furthermore, that some people are reluctant to carry out the act themselves. Resultantly, where assisted suicide is legal but euthanasia is not then fewer people end their lives. Euthanasia also carries the risk that doctors might practise non-voluntary euthanasia, where the patient is unable to make a request but the doctor judges it to be beneficial. This happens on a large scale in places such as the Netherlands and Belgium.

Nevertheless, once the line has been crossed and assisted suicide is legalised, this paves the way for the introduction of euthanasia – and the abuses associated with it. In a similar vein, even if euthanasia or assisted suicide is first legalised for a narrow, restricted group (such as those who are terminally ill) over time the conditions for eligibility will grow wider (such as to those who are chronically ill and disabled), because once it is accepted that some people have the right to end their lives, any restrictions on eligibility will ultimately be seen as arbitrary. This also is seen in the Netherlands and Belgium. Euthanasia or assisted suicide thus have an adverse effect on suicide prevention strategies among disabled people.

Euthanasia and assisted suicide seem like a compassionate response to someone who is close to death, and in great pain. Some think it would spare them ‘needless suffering’. However, one might first ask whether palliative care is already enough to at least mitigate, even if not eliminate completely, the physical suffering of the patient. The focus should be on adequate symptom relief to help the patient live their last few days or weeks as comfortably as possible, not to intentionally end life so as to avoid symptoms that could have been palliated.

Of course, our focus has to be broader than just physical pain. Most patients who request euthanasia/assisted suicide do so, not because of pain or the fear of it, but because of reasons such as feeling like a burden on those caring for them, or feeling that their lives have been stripped of dignity by illness, or realising that they can no longer participate in activities that once made life enjoyable. (These are some of the reasons we see, for instance, in annual reports published by the state of Oregon, which detail the reasons given by those requesting assisted suicide). In other words, euthanasia / assisted suicide often has to do, not with the fact of pain, which could be palliated but with whether life still seems worthwhile.

In response to such a situation, euthanasia / assisted suicide is not a truly compassionate response because it is an abandonment of the patient – a giving up of hope on someone who feels trapped by the negativity of their situation. It is to validate the patient in their feeling of hopelessness, and it represents a failure to help the patient find a pathway out of their difficulties.

Rather, if someone has lost enjoyable activities in life, the appropriate response is to help them find new activities they can enjoy and find meaning in. If someone feels lacking in dignity, they can still be helped to rediscover a sense of dignity, such as in the way we relate to them – examples of which would be: taking care how to address a person, helping them take care of their appearance, sharing information and involving others (insofar as that is what the person wants), asking the person about their wishes and feelings and responding honestly even if not every aspiration can be fulfilled. If someone feels like they are a burden on others, surely the best response is to affirm them that they are loved and they are worth it, that they are not in fact burdening anyone unduly.

This, in essence, is the path of authentic palliative care: to care for a patient unconditionally for as long as they live, and not to give up hope in them, even if they have, for a time, lost a sense of purpose. Euthanasia / assisted suicide embodies a different logic – caring for the patient is conditional on the patient seeing their own life as worthwhile.

The moral prohibition on taking innocent human life – one’s own or others’ – is fundamental to the ethical life. It is so basic that it can be difficult to articulate. It is not something we derive from other moral principles or norms, but is a foundational principle for thinking about ethics. All of us have a sense of the basic dignity and worth of every human being, such that we know human beings are not mere objects for use. In view of this we recognise that respecting human life is essential to living well in a community of citizens, and is one of the most basic principles of justice. A just society is therefore one that affords everyone equal protection from killing. This principle, founded on our common humanity, if applied consistently, excludes both the killing of others and the killing of oneself. Individuals in society may occasionally lose sight of their own dignity, but they still remain a member of the human community and should be helped to recover their sense of self-worth, not encouraged to kill themselves.

It can be difficult to see why suicide – and assistance of it – is wrong because of the way contemporary culture speaks about autonomy. Autonomy is often understood to mean the freedom to choose and have control over the conditions of one’s life and, with respect to the present issue, the conditions and timing of one’s death. While respect for autonomous choice is often a good thing, we need to recognise, however, that it must be complemented by a perspective on what it means to lead a flourishing life. Autonomous choice is important because all of us have different routes to flourishing as human beings, and freedom is essential for discovering our own path to flourishing. However, this freedom is not free-floating and finds its fulfilment only within our humanity. This presupposes the dignity of human life and thus the dignity of one’s own life. This is not a ‘limit’ imposed on freedom, but a paradigm within which freedom is meaningful. Freedom is a means to flourishing, it is not an end itself.

From the perspective of Catholic theology, this understanding of ethics takes on a deeper dimension. Our intrinsic dignity and potential for flourishing has a supernatural origin: each and every one of us is made in the image and likeness of God, each one of us is specially created by Him. Each one of us has the potential for union with God, both in this life and in Heaven, and that helps us understand yet another reason why intentionally taking the life of another is morally excluded. It is destroying the potential for so great a good, and over which we have no authority, for God alone is its source.

So often when euthanasia/assisted suicide is proffered as a ‘solution’ for a terminally ill patient, underlying it is a belief that the patient is past their best days, and that there is no more room for flourishing in their life. The Christian faith, by contrast, holds out the hope that there is always meaning, and always the possibility of spiritual union with God. Flourishing in one’s last days may look very different from flourishing during one’s prime, but with solidarity and support from one’s community even the dying can find a sense of fulfilment and peace.

There are various practical reasons as to why legalising euthanasia / assisted suicide would be dangerous. One of the most compelling reasons is that euthanasia / assisted suicide laws would jeopardise those who are suicidal and those with disabilities.

Legalising euthanasia / assisted suicide essentially creates a double-standard in the law and in suicide prevention. It creates two classes of people: those whose lives are ‘worth living’ and who therefore enjoy the full protection of the law in relation to homicide and assistance in suicide, and those whose lives are ‘not worth living’ such that the means of death should be made available to them. Although euthanasia / assisted suicide laws may start off with a narrow scope, what they cannot control is the fact that such laws sanction suicide as an acceptable response to problems of pain and hopelessness, and feelings of being a burden on others.

These problems are felt by people of all ages and conditions, and not just those who meet any legal criteria of euthanasia / assisted suicide. Hence, legalisation would endanger all those who struggle with suicidal thoughts. Suicide becomes progressively normalised and validated as a ‘solution’. The current evidence from the US, when comparing states with and without assisted suicide, suggests that legalising assisted suicide is associated with an overall increase in suicide rates, when counting both assisted and ‘unassisted’ suicides. Even the rate of unassisted suicide increases, for example, in Oregon, unassisted suicide among those aged 35-64 increased by 49% between 1999 and 2010 (compared with 28% nationally).

Euthanasia / assisted suicide would also fuel the impression that living with serious illness or disability, and in particular having to depend on others, is an indignity to the person. Although progress in disability rights over the past few decades has been encouraging, it remains the case that many people, as it is, find it difficult to see lives with disability as having much value or enjoyment. Legalising euthanasia / assisted suicide would encourage the thought that living with serious illness or disability is a wholly negative thing and is a legitimate grounds for taking one’s life.

Finally, it is worth considering how euthanasia / assisted suicide would fundamentally change the ethos of solidarity that is at the heart of healthcare. It shifts the focus from how we treat the patient and care for them in all circumstances, however serious their condition, to how we might eliminate the patient in order to eliminate the symptom or illness. This is not a person-centred approach to healthcare but a person-eliminating approach.

Most recent

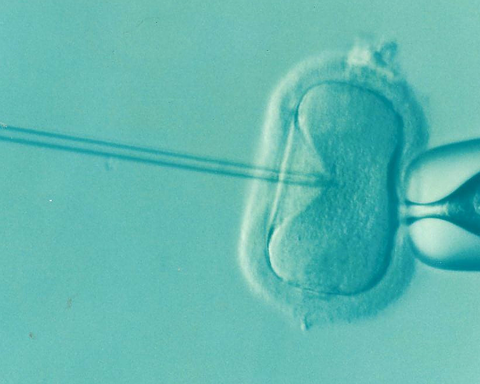

Bioethics in Brief: The Status of the Human Embryo

16 April 2022

Our ‘Bioethics in Brief’ on the Status of the Human Embryo.

Bioethics in Brief: IVF and Artificial Insemination

16 April 2022

Our ‘Bioethics in Brief’ on IVF and Artificial Insemination.

Sincerest Thanks for Your Support

Staff are grateful to all those who sustained the Centre in the past by their prayers and the generous financial support from trusts, organisations, communities and especially from individual donors, including the core funding that came through the Day for Life fund and so from the generosity of many thousands of parishioners. We would finally like to acknowledge the support the Centre has received from the Catholic community in Ireland, especially during the pandemic when second collections were not possible.

We would like to emphasise that, though the Centre is now closed, these donations have not been wasted but have helped educate and support generations of conscientious healthcare professionals, clerics, and lay people over almost 50 years. This support has also helped prevent repeated attempts to legalise euthanasia or assisted suicide in Britain and Ireland from 1993 till the end of the Centre’s work on 31 July 2025.