Bioethics in Brief: Principle of Double Effect

Bioethics In Brief – Principle Of Double EffectWhen making a moral decision, we often treat side-effects of our actions differently from effects we intend. For example, when giving criticism, we think it more problematic morally to hurt the person intentionally than merely to foresee that our words will cause them pain.

Sometimes we tolerate even very negative outcomes as a side-effect, in view of the good we are trying to do or the urgency of the situation. For example, we might foresee that selling some life-saving medicine to millions of people will sadly result in a very small number of people dying from rare allergic reactions. Intending these deaths, whether as an end itself or as a means to a further end, would be seriously wrong. But if these deaths are unintended side-effects, and our intention is to save many lives, then this may be a morally justifiable course of action.

What we intend versus what is a side-effect is not our only consideration, of course. We would also wish to consider whether the negative side-effects are proportionate to the good outcomes being intended. A small but significant risk of death from allergic reactions might be far less acceptable if, say, we are selling a medicine to control acne.

These remarks serve to remind us that the Principle of Double Effect (also known as the Doctrine of Double Effect or double effect reasoning) is not something obscure and artificial. Moral reasoning about the good and bad effects of our actions is something we do all the time, both in everyday situations and when making more complex decisions. This is because our actions always have effects we clearly foresee but do not intend.

Most of the time we do not reason about side-effects in a formalised way. But the Principle of Double Effect aims to set out how we reason about side-effects in a more systematic manner, as this can be particularly useful for dealing with more difficult cases. It comes in different versions, but the following is a representative list of conditions required by the Principle of Double Effect for our action to be justified:

- Our immediate act, informed by our immediate intention, must be good;

- Our further intention (the end we are seeking, what is motivating the action) must be good;

- Any bad effects must not be the means to the good outcomes we intend (so they must be side-effects rather than effects that are intended as part of a chain of reasoning);

- There must be a proportionate reason to tolerate the bad effects, in the good we are intending to bring about.

Note that the Principle of Double Effect cannot tell us what is right and wrong on its own; we can only use double effect reasoning together with a sound understanding of important moral norms, e.g., that it is always wrong intentionally to harm someone in a basic aspect of their well-being.

It is true that we sometimes point to a single, ‘ultimate’ intention when asked to clarify why we are acting the way we are. Nonetheless it is characteristic of our actions that they often have many steps of intention: for example, a nurse tasked with administering a vaccine would be intending to prepare the patient with the intention of injecting the patient, and this may be informed by the immediate intention of providing immunity to the patient, as well as the further intention of helping to control a national epidemic through this particular vaccination, among others. One can also have more than one intention for performing a single act. For example, the nurse can go to work each day with both an intention to earn a salary and an intention to heal.

The Principle of Double Effect matters because all our intentions matter. We cannot simply choose one intention as our ‘real’ intention and dismiss the rest as mere side-effects. Nor can we intentionally do what is wrong in order to bring about good. We must be honest about the precise plan of action before us for consideration and what, within that plan, counts as an intended effect and a mere side-effect. All our intentions in a course of action must be good or at least indifferent.

For example, ending or reducing suffering is a good intention, but not all means of achieving this outcome are morally justified. If the intentional killing of the innocent is always wrong, then killing a patient, even for the sake of ending suffering, would still be wrong. In the case of intentional killing, death cannot just be dismissed as an unwanted side-effect, where the ‘real’ intention is ending suffering; rather the killing is intended precisely as the means by which the patient’s suffering is ended. Hence it contravenes the Principle of Double Effect.

Read the Bioethics in Brief entry on Euthanasia.

No: the fourth step in double effect reasoning demands that negative side-effects are only tolerated when there is a proportionate reason. It is not a licence for accepting any kind of harm so long as we have the excuse of a good intention. To return to the example of selling a life-saving drug which has rare lethal side-effects, these might be tolerated because of the great number of people who would benefit from the drug being sold. But if studies indicated that the drug was not beneficial to most, and that seriously harmful side-effects were quite common, then such a drug should not be released. ‘Mere’ side-effects can still be out of all proportion to any good we can realistically expect.

It is therefore not the case that we can forget all about side-effects if all our intentions are morally right. To return to the case of end-of-life decisions mentioned in the last question, the intention of reducing suffering is a good one, and while euthanasia is morally excluded, palliative drugs could be a justifiable means of reducing suffering. Nonetheless such drugs may reduce someone’s awareness so they can no longer think clearly or interact with loved ones. Another means of reducing suffering could be the stopping of very painful or invasive treatment. But in stopping such treatment, this may result in the patient dying of their illness much earlier than if treatment were continued. Even if semiconsciousness or a hastened death are not intended by the one administering palliative drugs or withdrawing treatment, they are serious side-effects and one cannot simply assume that they are justified by the good intention of minimising suffering. It will depend on how these actions accord with each person’s circumstances, duties and wishes.

Analysing our decisions, especially difficult or weighty ones, with the Principle of Double Effect helps us be clear about our intentions and our motivations. It reminds us that morality is not just about coming to the right conclusion; it is also about making the right choice for the right reasons.

Read the Bioethics in Brief entry on Withdrawing and Refusing Treatment.

It is true that people often hide their intentions or admit to them selectively, claiming that only the good outcomes are really intended and that any bad outcomes are ‘mere’ side-effects. The purpose of formalising double-effect reasoning is to have a clear, step-by-step tool to help uncover where our real intentions are, and what cannot be passed off as a side-effect. People may try to hide their intentions from others, or from themselves, but double-effect reasoning is about what they in fact intend. What they intend is, moreover, often clear from what they say and do: juries, for example, are asked every day to judge the intentions of the accused on the basis of the evidence.

There is a difference between what we intend and what we emotionally welcome or emotionally regret. To begin with, regretting some outcome does not mean we don’t intend what we regret. Someone can kill a person with extreme reluctance, for example, but no less deliberately for that.

Conversely, welcoming an outcome does not mean we do intend that outcome. What we feel, and what we are intending, need to be carefully distinguished.

Take a case where doctors decide to take a patient off some course of treatment, not because they are intending the patient die but simply because the patient is not benefitting enough to justify the treatment’s burdens. When the patient dies, as it is foreseen they will, a bed will foreseeably be freed. To welcome the side-effect of freeing a hospital bed when the treatment is stopped is very different from intending to free the bed by stopping that treatment. On the other hand, the fact of welcome side effects (such as freeing up a bed) can represent a conflict of interest and it is important to ensure that the same decision would have been made even without the welcome side effect. One way to check our honesty about our intentions is to ask others what they would do in the circumstances.

Similarly, from the patient’s perspective, the patient may welcome the fact that death will come sooner – for example, a religious person may welcome the prospect of going to God more quickly. This does not in itself mean that the patient, in consenting to the treatment being stopped, intends to hasten death. Indeed, from a Christian perspective what matters is not to go to God sooner or later but to be in communion with God, a relationship wherein we accept God as Lord of life and death.

D. Solomon, ‘The Principle of Double Effect’ in The Encyclopaedia of Ethics (reproduced online)

Thomas A. Cavanaugh ‘Aquinas’s Account of Double Effect’ (1997). Philosophy. Paper 33.

G.E.M. Anscombe ‘Action, Intention and “Double Effect”’ in M. Geach & L. Gormally (eds.), Human Life, Action and Ethics. Exeter: Imprint Academic (2005)

Most recent

Bioethics in Brief: The Status of the Human Embryo

16 April 2022

Our ‘Bioethics in Brief’ on the Status of the Human Embryo.

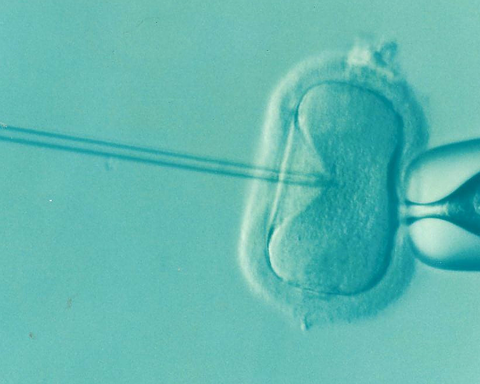

Bioethics in Brief: IVF and Artificial Insemination

16 April 2022

Our ‘Bioethics in Brief’ on IVF and Artificial Insemination.

Sincerest Thanks for Your Support

Staff are grateful to all those who sustained the Centre in the past by their prayers and the generous financial support from trusts, organisations, communities and especially from individual donors, including the core funding that came through the Day for Life fund and so from the generosity of many thousands of parishioners. We would finally like to acknowledge the support the Centre has received from the Catholic community in Ireland, especially during the pandemic when second collections were not possible.

We would like to emphasise that, though the Centre is now closed, these donations have not been wasted but have helped educate and support generations of conscientious healthcare professionals, clerics, and lay people over almost 50 years. This support has also helped prevent repeated attempts to legalise euthanasia or assisted suicide in Britain and Ireland from 1993 till the end of the Centre’s work on 31 July 2025.