Bioethics in Brief: The Status of the Human Embryo

Bioethics In Brief – The Status Of The Human EmbryoWhat is an embryo? The word seems to be the name of a kind of thing, like the word ‘mammal’. There are different species of mammal, such as mice, kangaroos and human beings, but we can say of each one – this is a mammal. I am a mammal and so are you. This is the class of animals to which we belong. In a similar way we might imagine that ‘embryo’ is a class of living beings and it comes in specific types – mouse embryos, kangaroo embryos or human embryos – but of each one we can say ‘this is an embryo’.

However, this way of talking is misleading. To call something an embryo is not to identify the kind of being it is, its class or nature, but is rather to identify its phase of development. The word ‘embryo’ is like ‘infant’ or ‘adolescent’, ‘youngster’ or ‘senior’, ‘hatchling’ or ‘fledgling’. It is a description, not of the essence or nature of a thing, but of its stage of life. So we can say ‘I am a mammal’, it is my nature, but ‘I was once an infant’ or ‘I hope to live to be a senior’, these are stages on my life journey.

This would be clearer if we used the adjective, ‘embryonic’ instead of the noun ‘embryo’. Mouse embryos and human embryos are embryonic mice and embryonic human beings. As a human infant is simply a very young human being, a human embryo is an even younger human being.).

An embryo is the very first stage in the development of a multicellular organism which, in the typical case, begins as a single fertilised cell, and develops though the multiplication and differentiation of cells. First internal organs (e.g. heart and brain) and then externally visible organs and structures develop according to the species to which the organism belongs (fingers and toes or wings and beaks). Different species of animal look very similar to one another at the embryonic stage but in reality they are always different.

This should remind us of another important truth: people are animals too. We often use the word ‘animal’ in contrast to human being. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, for example, does not campaign to prevent cruelty to human beings only to non-human animals. Certainly, human beings are unique among animals in many ways, only human beings could even ask themselves the question as to whether they were unique. Other animals can signal to one another, to warn of danger or attract a mate, but they do not think about life and death and God, as far as we can tell. At the same time, homo sapiens is a species of animal, we are members of the animal kingdom, of the phylum chordata, class mammalia, the order primates, and species homo sapiens.

It is because we are animals that we eat and sleep, conceive and nurture offspring and eventually die. It is because we are animals that we have a life-cycle. We can reflect on our beginnings and endings in ways that no other animal can, as far as we know. We can welcome conception and birth and plan for decline and death, but the reason we come to be and pass away is that we are animals. And the first stage in the life of the kind of animal we are is the embryonic stage. Each of us was once an infant and, before this, each of us was an embryo.

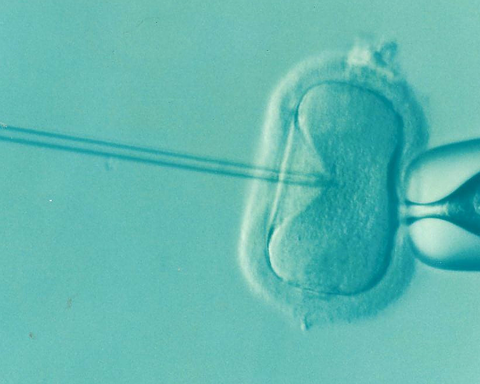

Every one of us has passed through many phases of life, embryonic, foetal, newborn infant, toddler, adolescent, to reach our present stage of life. I was once a new-born baby. I have no memory of it but my mother has embarrassing photographs to which she can point and say, ‘this was you as a baby’. These days some people’s parents also have ultrasound pictures of them in the womb and some people, who were conceived by IVF, even have a picture of themselves as an embryo so their mother can say ‘Look – that is you as an embryo before they put you inside me’.

What then is the significance of destroying a human embryo? It is destroying a human being at the first stage of his or her life. I was once a baby and had you killed that baby you would have killed me and I would not have been here today. At the embryonic stage, there are no feelings to hurt, no pain or fear, but there can still be injustice. To destroy an human embryo is to kill a human being, and this is a wrong that cannot be undone. If I take someone’s property I can return it but if I take someone’s life this is something no human power can restore.

We understand what the human person is both by our reason and by the light of divine revelation. The human person is created in the image and likeness of God (Genesis 1:26), which means ‘in the communion of persons, in the likeness of the unity of the divine persons among themselves’ (Catechism, §1702). The human person is created with a calling to love and serve God, and is destined for a life of communion with other human persons, and ultimately for communion with the divine persons: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. It is in virtue of having a soul that the human being is a human person, whose dignity derives from being created in the image and likeness of God and ‘willed for its own sake’ (Catechism, § 1703).

All cultures have rules against killing other human beings, but in many cultures these rules have exceptions and it is typically the very young, the very old and people with impairments who are vulnerable to having their lives ended. Such exceptions remove protections from vulnerable classes of people, and do so because they are viewed as a burden or an obstacle to the happiness of others. In contrast the teaching of the Catholic Church is very clear that the right to protection from being killed is something that holds from the first moment of conception.

People sometimes say that human embryos do not have a rational soul on the basis that St Thomas Aquinas said that the rational soul was not created by God until forty days after conception in the case of male children or ninety days in the case of female children. However, Aquinas took this rather strange idea from Aristotle who based it on biological theories that are completely outdated. This was before microscopes had been invented, when no one had seen human sperm or eggs or witnessed the process of fertilisation and it was before the understanding of modern genetics. We now know, as Aquinas did not, that the process of embryonic development is directed from within. The consensus of Catholic theologians is that, taking into account modern science, the rational soul is present from the moment of fertilisation. It should also be noticed that even though Thomas Aquinas thought that the early embryo did not have a rational soul, he thought the embryo should be protected from intentional killing as soon as it began to exist.

The official teaching of the Church has been cautious about defining when the soul is created by God but has been constant in teaching that the human embryo is to be given the protection due to a human person:

‘Certainly no experimental datum can be in itself sufficient to bring us to the recognition of a spiritual soul; nevertheless, the conclusions of science regarding the human embryo provide a valuable indication for discerning by the use of reason a personal presence at the moment of this first appearance of a human life: how could a human individual not be a human person? The Magisterium has not expressly committed itself to an affirmation of a philosophical nature, but it constantly reaffirms the moral condemnation of any kind of procured abortion. This teaching has not been changed and is unchangeable’. (Donum vitae I.1)

Most people can imagine the moment when they were conceived, when one egg and one particular sperm fused, and can say ‘that embryo was me’. From that moment the same living being grew and developed before and then after birth.

However, identical twins cannot say this. If an early embryo splits to generate twins then these two cannot both be right if they later say ‘that embryo was me’. That embryo cannot be the same person as both of them, cannot have the same soul as both of them.

Some people argue that this shows that the early embryo is not yet a human individual because human individuals cannot split in two. It is for this reason, among others, that the law in the United Kingdom permits destructive experimentation on human embryos in the first 14 days. This is the phase of life when the embryo can split into two.

The argument from twinning does not show that the embryo cannot be a person. We could just say that science has shown that some human persons can split into two, but only when they are very young. The fact that one living being gives rise to two living beings does not show that it was not ‘really’ one. Perhaps one embryo is the original and one is a new living being, or perhaps both embryos are new and the original one has died, or perhaps both were somehow present potentially. With twinning there is a fact of the matter about which one is which, even if we do not know. However, while we may be perplexed about which was the same embryo after twinning, it would be wrong to kill a person just because we unsure about who they were.

What is essential to remember is that an embryo is the first stage in the development of a living being and a human embryo is thus an embryonic human being with inherent dignity. Every human being is created by God in God’s own image and likeness and has an immortal soul and an eternal destiny. Every human embryo is owed the respect and protection due to a human person.

Most recent

Bioethics in Brief: IVF and Artificial Insemination

16 April 2022

Our ‘Bioethics in Brief’ on IVF and Artificial Insemination.

Bioethics in Brief: Contraception and Natural Family Planning

16 April 2022

Our ‘Bioethics in Brief’ on the Contraception and Natural Family Planning.

Sincerest Thanks for Your Support

Staff are grateful to all those who sustained the Centre in the past by their prayers and the generous financial support from trusts, organisations, communities and especially from individual donors, including the core funding that came through the Day for Life fund and so from the generosity of many thousands of parishioners. We would finally like to acknowledge the support the Centre has received from the Catholic community in Ireland, especially during the pandemic when second collections were not possible.

We would like to emphasise that, though the Centre is now closed, these donations have not been wasted but have helped educate and support generations of conscientious healthcare professionals, clerics, and lay people over almost 50 years. This support has also helped prevent repeated attempts to legalise euthanasia or assisted suicide in Britain and Ireland from 1993 till the end of the Centre’s work on 31 July 2025.