Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide: A Guide to the Evidence

This evidence guide has been written to inform the debate about whether to legalise physician assisted suicide or euthanasia in the United Kingdom. Most of the sources cited here are also relevant to the debates on assisted suicide or euthanasia in other countries.

You can skim to get a sense of the different issues at stake and where to find further information, especially the most reliable information that is freely available online.

This guide aims to be useful for:

- students (especially of the medical professions, law, philosophy, and bioethics)

- scholars

- research assistants to officials or parliamentarians.

More than this, it is offered to anyone who is concerned about these issues and wishes to assess the evidence.

It is important to remember, as has recently been pointed out, ‘that the medical literature is, in general, favourably disposed toward the empirical and the new [… resultantly] articles defending the ethical status quo (i.e., against PAS) tend to be shut out of the medical literature because they are not reporting anything new and, therefore, cannot have any data. The result is an impression of growing acceptance of PAS, but it really represents an artefact of a scientific bias’. It is hoped that this guide contributes to redressing this scientific bias.

Along with references for the source-data and official reports on assisted suicide and euthanasia in various countries, it identifies some useful articles that have been published in Peer Review Journals (PRJ). Publishing in a PRJ is no guarantee of the truth of an article’s conclusions, for especially in law, ethics and public policy academics frequently argue for opposite conclusions. However, being published in a PRJ is a sign that other academics have considered the argument to be well-structured and the sources of evidence to be clearly identified. This provides a good starting point for debate. Unfortunately, most PRJ material is not free to the general reader but is available only through universities or by subscription. Nevertheless, some PRJ articles are free online and sometimes there are freely available discussions based on the article. At a minimum the abstract of the article will generally be available free online. In this bibliography, all PRJ articles will be identified with an asterisk*. Where the full text of a PRJ is freely available this will be indicated by * (full text available). Where the published version is not freely available, a pre- or post-print draft occasionally will be. This means that the full text can be read, but the article has none of the publisher’s formatting.

Many articles on euthanasia and assisted suicide have been published since the original version of this evidence guide in 2015. We have updated the guide to include new literature and the changes to legislation regarding euthanasia and assisted suicide throughout the world since that time. The guide is intended to be indicative rather than fully comprehensive, and we intend to update the resources periodically in the future.

DA Jones, R Gay, CM Wojtulewicz, & M Fox

Oxford, November 2024

Abbreviations

EAS = euthanasia and/or assisted suicide.

PAS / AS = physician-assisted suicide / assisted suicide

Introduction

Since 1990 within the United Kingdom there have been four parliamentary reports on assisted euthanasia or suicide. Reports were published in 1993, 2005, 2015 (Scotland) and 2024 (House of Commons). The review of Scottish Health, Social Care and Sport Committee (est. June 2021) is ongoing.

House of Lords Select Committee on Medical Ethics (HL Paper 21-I of 1993-4). There is no copy of the report available online, but a summary was provided by Lord Walton of Detchant (its chair) in a statement to the House of Lords recorded in Hansard.

(HL Deb 09 May 1994 vol 554 cc1344-412).

House of Lords Assisted Dying for the Terminally Ill Committee 5 April 2005 (Mackay Committee) On this committee’s findings see also I Finlay, VJ Wheatley, and C Izdebski. ‘The House of Lords Select Committee on the Assisted Dying for the Terminally Ill Bill: implications for specialist palliative care.’ Palliative medicine 19.6 (2005): 444-453.*

Scottish Parliament Health and Sport Committee 6th Report, 2015 (Session 4): Stage 1 Report on Assisted Suicide (Scotland) Bill. This Committee was ‘not persuaded by the argument that the lack of certainty in the existing law on assisted suicide makes it desirable to legislate to permit assisted suicide... there are ways of responding to suffering (such as increased focus on palliative care and on supporting those with disabilities), which do not raise the kind of concerns about crossing a legal and ethical “Rubicon” that are raised by assisted suicide’. [292, 294]

Devyani Gajjar and Abbi Hobbs, Assisted dying, UK Parliament POSTbrief 47, 26 September 2022. The Centre contributed to this POSTbrief, but does not thereby endorse it. Nevertheless it is included as useful material and is relatively balanced.

House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee, Assisted Dying/Assisted Suicide, Second Report of Session 2023-24, HC 321, 20 February 2024. The report does not conclude that current law on assisted suicide needs to change, nor that a Citizens’ Jury should be established, nor that there should be a referendum or parliamentary debate on the issue. The report contains much useful material, though there is unevenness in the level of analysis (some witnesses’ claims are not scrutinised), flaws in the summary of evidence, and some glaring omissions (e.g. effect of law change on suicide prevention among older or seriously-ill people). For more detail see the Anscombe Bioethics Centre press release on the report.

The Human Rights (Joint Committee) on Human Rights and Assisted Dying, correspondence and oral evidence (May-July 2023) fed into the Health and Social Care Committee report (HC 321) and is worthy of note. Particularly significant is the letter (dated 8th June 2023) of the Chair of the Joint Committee on Human Rights, Joanna Cherry KC MP, which concluded that this was a matter for Parliament and that human rights considerations neither required nor precluded a change in the law.

Although the Scottish Health, Social Care and Sport Committee has yet to produce a report, it has nonetheless released a summary analysis of responses to its consultation.

Current challenges in the culture of healthcare in the UK

If legalised, assisted suicide or euthanasia would be implemented in the context of the NHS. In this regard it is important to be realistic about the current state of healthcare in the UK and failures that can occur and that have occurred, for example, in Mid Staffordshire and in the implementation of the Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying Patient. These problems were not confined to one Trust or one Pathway but reflect cultural challenges within the NHS. How might assisted suicide or euthanasia be implemented in an environment of targets and ‘tick-boxes’ that sometimes operate to the detriment of patient care?

Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry (Francis Report)

Independent Review of the Liverpool Care Pathway: More Care, Less Pathway (Neuberger Report)

Introduction

Statistics for rates and characteristics of death by assisted suicide or euthanasia are available for twenty-two jurisdictions: Canada, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Spain, New Zealand, and all six Australian states, and, in the USA, the District of Columbia, and the states of California, Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Maine, New Jersey, Vermont and Washington. Assisted suicide is legal in Montana and New Mexico, but there are no official reports on the practice. There are also no official reports from Austria, Colombia, or Germany.

Such statistics are only as reliable as the questions asked and the means of data collection and in all cases rely on self-reporting. In Flanders (Belgium) it has been shown that official figures underestimate rates by approximately 50% (see section 5.4 below). Official reports tend to gloss the figures and readers should beware of ‘spin.’ Nevertheless, with these caveats, official figures remain an important source of evidence for the impact of legalising assisted suicide or euthanasia.

Europe

In Belgium euthanasia was legalised in 2002 and reports have been produced every two years. These are available (in French) here.

In Luxembourg euthanasia was legalised in 2009 and reports are produced every two years. Luxembourg has a small population (less than 1% of the UK population) and thus the number of cases is small. Nevertheless, over the years it is possible to see some patterns (a general increase in cases, an increase in non-cancer cases, more cases of women than men). To date seven reports have been issued, the latest being the report for 2021-2022.

In the Netherlands euthanasia was effectively decriminalised by a court decision in 1984. This was the basis of a legal statute in 2001 legalising euthanasia and physician assisted suicide. Since 2002 the Netherlands has produced an annual report on the cases notified to the five regional euthanasia committees. These are available (in English once the year is selected).

In Switzerland, since 1942, inciting or assisting suicide has been illegal when it is for selfish motives (such as financial gain). Since 1982 this law has provided legal space for the organisation EXIT to promote assisted suicide for those ‘with unbearable symptoms or with unacceptable disabilities’. There are two government reports from the Federal Statistical Office, one in 2012 and latest, for 2014, published in 2016 and revised in 2017. Dignitas has released statistics from 1998-2023.

North America

Canada passed euthanasia and assisted suicide into law in 2016 (termed ‘medical assistance in dying’ or MAID). Further changes in the law, widening eligibility criteria, were introduced in March 2021 (though not effective until March 2023). The Second Annual Report on Medical Assistance in Dying (2020) shows that ‘MAID’ deaths increased by 34.2% from 2019.

The District of Columbia legalised assisted suicide in 2016 and has produced one statistics report in 2018.

California legalised assisted suicide in 2015 and has produced reports each year since. They can be found here.

Colorado legalised assisted suicide in 2016, and has produced reports each year since. They can be found here.

Hawaii passed assisted suicide into law in 2018, which came into effect in January 2019. The 2019 and 2020 legislative reports can be found here.

Oregon legalised physician assisted suicide in 1997 and produces annual reports. Helpfully the latest report (2021) includes data from previous years. Note that the figure for the number of deaths in the most recent year covered by the report will generally be inaccurate as deaths are recorded against the year of the lethal prescription. For example, if a lethal prescription given in 2012 were used in 2013 the death would be recorded as due to assisted suicide in the 2012 figures. Reports from all individual years can be accessed here.

Maine introduced assisted suicide in 2019 and its reports can be found here.

New Jersey also passed assisted suicide into law in 2019 and its 2019 and 2020 data summaries can be found here.

Vermont legalised physician assisted suicide in 2013 for terminally ill patients. The latest report can be seen here (issued Jan 15 2022).

Washington legalised physician assisted suicide in 2009 following the Oregon model (Washington borders Oregon and to a great extent shares a common culture and history). Washington also produces annual reports.

Oceania

Victoria (Australia) legalised euthanasia and assisted suicide (under the umbrella term ‘voluntary assisted dying’ or VAD) in 2017, which came into effect in June 2019. Statistics are issued approximately every 6 months, and the data can be found here.

There are common patterns which emerge in each of these jurisdictions: in every jurisdiction numbers have increased over time and continue to do so; there has also been a shift from permitting assisted suicide for cancer victims to include other diseases. In Europe this includes non-terminal conditions such as neuro-psychiatric conditions and multiple co-morbidities (for example, those associated with old age). Supposed safeguards such as psychiatric referral have also declined in frequency (see below for further details). Essentially, the practice has become more widespread and more routine.

Introduction

Within the political debate on assisted suicide and euthanasia, both sides, but especially advocates of a change in the law, frequently appeal to surveys of public opinion. In polls, there is a consistent majority of public opinion that expresses support for legalising assisted suicide or euthanasia. There are, however, important caveats to this, not least the effect of wording in polls, and differences between those who 'strongly support' legalisation (which is always a minority) and those who 'somewhat support' it.

Polling data and research demonstrate the complicated nature of public opinion on the matter.

The Briefing Paper (above) analyses evidence from bi-monthly tracker surveys and from the British Social Attitudes survey to show that public opinion on ‘assisted suicide’ has remained largely stable over recent years. There has been no groundswell of opinion in favour. If anything, there has been a decline in those who ‘strongly support’ a change in the law, down from 49% to 31%.

The analysis of several different polls reveals a much more complicated than the headlines claim: only a minority strongly support legalisation, fewer than half want MPs to vote in favour, and very few people think this should be a priority for the Government. At the same time many had misgivings: 53% were concerned that vulnerable people would apply for assisted dying because they felt they were ‘a burden to others,’ while 75% thought the NHS was ‘currently not in a fit state’ to provide assisted suicide.

There is also widespread confusion, with surveys showing between 39% and 42% of people think that ‘assisted dying’ refers to withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment.

Policy Institute and the Complex Life and Death Decisions (CLADD) group at King’s College London, in collaboration with Focaldata (October 2024). This survey found that although ‘two-thirds say they want this Parliament to legalise assisted dying, less than half want their MP to actually vote for it’. 45% think their MP should be compelled to legalise it, whereas 29% want their MP to vote following his or her conscience.

Whitestone Insight Poll for Living & Dying Well (LDW) (July 2024). The poll indicates the complicated nature of public opinion. 56% of respondents ‘support legalising assisted dying/assisted suicide (AD/AS) in principle but feel there are too many complicating factors to make it a practical and safe option to implement in Britain’.

Opinium Poll for Dignity in Dying (March 2024). 75% were in support of a change in the law, and 14% against. This is actually a decline compared to some earlier polls. Note additionally that the questions refer to ‘assisted dying’ or ‘assisted death’ rather than ‘assisted suicide’—see below on wording of polls for why this matters.

It should be noted that Scottish support has reduced, see D.A. Jones, ‘Scottish support for assisted dying/assisted suicide is ebbing away’ Journal of Medical Ethics Forum 15 April 2024.

Ipsos-Mori Poll for The Economist (June 2015)

80% believe those accompanying a family member or friend abroad to receive assisted suicide should not be prosecuted. This drops to 74% when informed that current law in England and Wales is that assistance is punishable by up to 14 years in prison. 65% think the law should be changed to permit assistance in travelling abroad, see:

Ipsos-Mori Poll for Dignity in Dying (June 2009)

A 2019 poll commissioned by Dignity in Dying shows net support for assisted suicide law at 84%; but it must be noted that the procedure is referred to as ‘assisted dying’ rather than ‘assisted suicide’ (see the section below on wording of polls):

Populus Poll for Dignity in Dying (March 2019)

See also:

It should be noted that 73% think there ‘is a difference between a terminally ill adult seeking assistance to end their life and suicide’, see YouGov / Dignity in Dying (August 2021). However, the proposed legislation has the effect of amending the Suicide Act 1961 (as amended by the Coroners and Justice Act 2009).

On the issue of correct terminology and the use of euphemism, see:

In the UK, 78% are concerned that, as a society, as much as possible ought to be done to reduce suicide rates. 51% are concerned that people would see themselves as a burden and feel pressured into taking their own life if assisted suicide were legal, see:

ComRes Care Not Killing Assisted Suicide Poll (February 2019)

In a 2018 poll, although 75% were in favour of a change in the law, 60% did not know anyone close to them who had died who would have considered assisted suicide had it been available to them, see:

ComRes Daily Mirror Assisted Dying Poll (June 2018)

When participants are exposed to counter arguments to legislation, support wavers. In one poll from 73% to 43%:

Care Not Killing, “‘Assisted Dying’ and Public Opinion” (2014)

ComRes CARE Assisted Suicide Poll (2014)

The Mackay committee produced a very useful critical review on the state of evidence at that time (2005) in relation to public opinion on assisted suicide and euthanasia (Chapter 6 and Appendix 7).

‘The key conclusion of this report is that, although some idea of the basic attitude of the general public is available through research sources, this does not amount to an authentic picture of public opinion which is in any way comprehensive. Deliberative research techniques, unused so far for this subject, which can produce an account of informed public opinion, are recommended if a proper understanding of public opinion is to be achieved.’ (Appendix 7, para 17)

In 2022, it remains the case that ‘Research sponsors frequently appear to have been more concerned to achieve statistics for media consumption than to work towards achieving a comprehensive understanding of public and health sector attitudes’ (Appendix 7, para 2).

The flaws in most yes/no polls are methodological and are not corrected merely by conducting more polls of a similar kind. Qualitative research is needed to uncover the complexities of the issue and/or the complexities of people’s attitudes to the issue. For example, a study in the Journal of Medical Ethics showed that, if people were given a range of choices (and not just one), more individuals were in favour of legal sanctions against euthanasia than were in support of it.

This complexity is also shown in qualitative research with nurses and with dying cancer patients. See here:

Jaklin, A., N. Olver, and I. Eliott, ‘Dying Cancer Patients Talk about Physician and Patient Roles in DNR Decision Making’. Health Expectations 14, no. 2 (2011): 147–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00630.x * (full text available).

It is worth highlighting the following conclusion from the latter study: ‘Survey studies showing majority support for euthanasia have typically required individuals to make judgements about hypothetical and abstracted scenarios. Under such conditions, individuals are likely to draw upon the readily available and socially approved discourses of autonomy and compassion, and voice approval. To conclude that this legitimises euthanasia as social policy is to deny the import of other factors that feature when individuals have opportunity to do more than endorse or reject euthanasia’.

These complexities are by no means peculiar to the issues of assisted suicide and euthanasia, they apply more generally to use of public opinion in ethical debates around public policy. For such reasons government engagement with the public typically employs mixed methods: public events, open online consultations, stakeholder events, and representative opinion polls. The UK government’s Code of Practice on Consultation makes it clear that consideration of public opinion should give particular weight to the views of ‘any groups or sectors... that may be disproportionately affected by the proposals’ (3.4). [In the case of assisted suicide and euthanasia this would be people who are dying, those who are living with disabilities, their carers, and healthcare professionals, especially doctors who care for the dying.] Consultations should not just ask for conclusions but ‘the evidence given by consultees to back up their arguments. Analysing consultation responses is primarily a qualitative rather than a quantitative exercise’ (6.1).

These principles of good practice should apply also when judging the competing claims to how ‘the public’ thinks of assisted suicide and euthanasia.

The misrepresentation of polling data is discussed by Andrew Hawkins in ‘Polling on Assisted Suicide: The Misuse of Public Opinion’ in The Reality of Assisted Dying: Understanding the Issues, eds., Finlay I & Hughes J, (Open University Press, Maidenhead: 2024).

Wording of polls

For research purposes it is necessary to consider the wording used in polls and to consider what effect this may have on the results. This means not only the choice of terminology (e.g., ‘assisted dying’ vs ‘assisted suicide’) but whether and to what extent questions inform the participants. Some polls measure the difference more information has. The 2024 poll for LDW, for instance, highlighted that public opinion changes when people are ‘confronted with evidence from where it is legal’ (see link above).

Support for euthanasia and assisted suicide in public opinion polls is, according to Grove et al., subject to ‘over 20% variation in mean support’ where there are ‘increasing levels of favourable wording’, and that ‘[a]llusions to hopelessness had an especially strong effect on increasing support for EPAS [euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide]’:

Kirchhoffer, David G. and Chi-Wai Lui, ‘Public reasoning about voluntary assisted dying: An analysis of submissions to the Queensland Parliament, Australia’. Bioethics 35, no. 1 (2020): 105-16. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12777.* (full text available) The article analyses in detail language used and concludes that there is a ‘need for caution in relying on surveys of public opinion to make laws concerning VAD [voluntary assisted dying]. Sound normative reasoning remains vital.’

See also: L. Parkinson et al. ‘Cancer patients’ attitudes towards euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: The influence of question wording and patients’ own definitions on responses’, Journal of Bioethical Enquiry, 2(2) (2005): 82-89 * (full text available).

Aghababaei, Naser, Hojjatollah Farahani, and Javad Hatami. ‘Euthanasia Attitude; A Comparison of Two Scales’. Journal of Medical Ethics and History of Medicine 4 (12 October 2011): 9. * (full text available).

Another reason to be cautious of such polling (and opinion polls more generally) is that they do not necessarily reflect how people actually vote when given the opportunity. Most ballot initiatives in the USA on this issue have in fact failed, despite opinion polls seeming to show strong support. Those which have passed (Oregon, Washington, and Colorado) only secured modest majorities (51%, 58%, and 65% respectively).

Introduction

Whereas simple yes / no public opinion polls typically find a significant majority in favour of legalising assisted suicide or euthanasia, opinion among the medical profession is generally opposed.

In March 2019, the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) adopted a position of neutrality, based on a survey of fellows’ and members’ views. 43.4% thought the RCP should be opposed to a change in the law, 31.6% thought the RCP should support such a change, and 25% thought the RCP should be neutral. While this shift was interpreted by some in the media as a move in favour of legalisation, they stated that, ‘So that there can be no doubt, the RCP clarifies that it does not support a change in the law to permit assisted dying at the present time’.

Although the Royal College of Radiographers (RCR) does not hold a position on ‘assisted dying’, in 2019 they polled their fellows and members, asking what they thought the RCR Faculty of Clinical Oncology’s position should be on whether or not there should be a change in the law on ‘assisted dying’. The response rate was only 34% (540 complete responses), but 42.9% thought the RCR position should be ‘opposed’, 26.9% thought ‘in favour’, and 30.3% thought ‘neutral’.

The 70th General Assembly of the World Medical Association (October 2019) stated that ‘the WMA is firmly opposed to euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide’.

In 2020, the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) decided not to change its position of opposition to ‘assisted dying’, and would not review this for five years ‘unless there are significant developments’.

The decision was based on a 2019 Savanta ComRes consultation of RCGP members. Only 41% of respondents thought the RCGP should support a change in the law if ‘there is a regulatory framework and appropriate safeguarding processes in place’. Only 7% thought ‘GPs should be responsible for prescribing drugs for assisted dying (provided that a formal verification process is in place)’. There was also reluctance to the idea of referring a patient (only 46% support) or supporting/counselling whilst a decision is being made (only 42% support).

The British Medical Association (BMA) changed its position on 14th September 2021 from opposition to a position of neutrality on the subject of ‘physician-assisted dying’. This was preceded by a survey of BMA members’ views on the subject (Kantar, February 2020). The response rate was 19.35% (28,986 members out of 152,004).

50% of respondents were personally supportive of ‘physician-assisted dying’ as a practice. But the percentage of those willing to participate in some way in ‘physician-assisted dying’ was only 36%. There is stronger opposition in general to euthanasia than there is for assisted suicide.

The Association for Palliative Medicine of Great Britain and Ireland (APM) urged parliamentarians to reject the Assisted Dying Bill [HL] 2021 in a briefing statement in October 2021. A 2021 APM member survey found that 67% of respondents thought that ‘patients and families think they are definitely or probably practicing covert euthanasia’, showing a prevalence of misconceptions about palliative care among the public. 87% ‘felt there has not been good enough press coverage of good deaths’.

A study in New Zealand showed that medical students were less likely to support euthanasia / assisted suicide towards the end of their studies compared with the beginning, which is ‘most likely due to their time in medical education’, see:

Nie, Luke, Kelby Smith-Han, Ella Iosua, and Simon Walker. ‘New Zealand Medical Students’ Views of Euthanasia/Assisted Dying across Different Year Levels’. BMC Medical Education 21, no. 1 (23 February 2021): 125. * (full text available).

Research in Norway in 2014 and 2016 shows that only 9.1% of doctors in the Institute for Studies of the Medical Profession ‘strongly agree’ or ‘partially agree’ with PAS:

Disparity between support and willingness to be involved

Evidence from Canada and Australia show high levels of disparity between those who support euthanasia/assisted suicide in principle, and those who are willing to participate in the procedure.

Sellars, Marcus, Mark Tacey, Rosalind McDougall, Barbara Hayes, Bridget Pratt, Courtney Hempton, Karen Detering, et al. ‘Support for and Willingness to Be Involved in Voluntary Assisted Dying: A Multisite, Cross-Sectional Survey Study of Clinicians in Victoria, Australia’. Internal Medicine Journal 51, no. 10 (2021): 1619-1628. * (embargoed until 01/10/2022)

Bouthillier, Marie-Eve, and Lucie Opatrny. ‘A Qualitative Study of Physicians’ Conscientious Objections to Medical Aid in Dying’. Palliative Medicine 33, no. 9 (October 2019): 1212–20. * (full text available).

The RCR poll of fellows and members in 2019 (see above) showed that 37.3% supported a change in the law to permit ‘assisted dying’, with 46.9% opposed. But when asked, regardless of support or opposition, if they would ‘participate directly’ should the law change, 56.1% said ‘no’ and 23.2% said ‘yes’.

The American Medical Association (AMA) adopted a policy position in 2019 to affirm that physicians may provide medical assistance in dying 'according to the dictates of their conscience without violating their professional obligations.'

However, an attempt to change the AMA's official position on physician-assisted suicide from 'opposed' to 'neutral' was rejected by its House of Delegates in November 2023.

Religious views on End-of-Life Issues

Pew Research Center, ‘Religious Groups’ Views on End-of-Life Issues’, November 21 2013.

In the UK, a study of the influence of religious beliefs on medical students’ attitudes to EAS showed that among those surveyed (with 68.5% professing belief in God), ‘the majority of students did not agree with euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the study scenario. Those who had a belief in god were more likely to disagree with actions that hasten death. The findings show that this was particularly the case with students from a Muslim background’. See:

Pomfret, Suzie, Shaya Mufti, and Clive Seale. ‘Medical Students and End-of-Life Decisions: The Influence of Religion’. Future Healthc J 5, no. 1 (1 February 2018): 25–29. https://doi.org/10.7861/futurehosp.5-1-25. * (full text available)

Introduction

Euthanasia and / or assisted suicide is legal in a number of places in the world. In some cases, legalisation happened nearly 30 years ago, although there has been a rapid growth in the last 10 years in the number of jurisdictions where, in particular, assisted suicide is permitted under certain conditions.

The British Medical Association have produced a map which shows at a glance where euthanasia and / or assisted suicide is legal. This map does not include Ecuador, which legalised euthanasia in 2024.

Commonly there is a requirement for reporting data and monitoring of practice in places where EAS is permitted (see section 2 above). Such reports, along with other data and analysis provides a body of evidence which highlights several aspects of the practice, including reasons for concern. This section provides information from such data which highlight problematic aspects of euthanasia and assisted.

Ever increasing number of people dying by EAS following legalisation

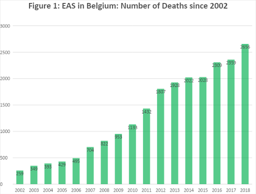

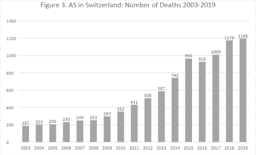

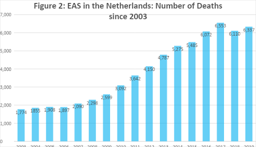

Belgium and the Netherlands provide data over a long period of time, and therefore are amongst the most studied jurisdictions. An obvious cause of concern from both places is that EAS have shown large incremental increases over time.

Figures 1 and 2 below show the number of deaths attributed to EAS since the early 2000s in Belgium and the Netherlands, showing the increasing numbers over time. Looking more closely, comparing the number of deaths in each country over the ten-year period between 2008 and 2018, we see significant increases, with EAS making up:

- 0.78% of deaths in Belgium in 2008, rising to 2.4% of deaths by 2018

- 1.7% of deaths in 2008 and 3.9% of deaths in 2018 in the Netherlands (4.1% in 2020)

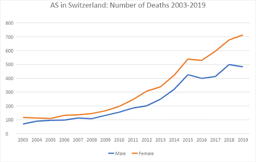

In other jurisdictions, similar increases are seen. In Canada, for example, the increase in deaths since legalisation of PAS was very steep, rising from 1,018 in 2016 to 7,595 in 2020, a 7.5-fold increase in just four years, representing 0.38% of all deaths in 2016, increasing to 2.5% of all deaths in 2020. In Switzerland, between 2009 and 2019, the number of AS deaths increased more than 4-fold from 297 to 1,196 (see Figure 3 below).

The number of deaths due to AS in Canada in 2020 is the highest total number of deaths due to EAS reported in any country in the world at 7,595, with the Netherlands the next highest number, recording its highest ever number at 6,938 in 2020. It should be a cause for concern that in places where EAS is legal to practice, increasing numbers of people choose to end their own lives, or to ask for others to end them for them.

Terminology of the Legislation

In many places where EAS is legally practised, the language surrounding the legislation could be argued to minimise the reality of the practices employed and the nature of the acts involved; namely a direct act by a medical practitioner with the intention of ending the life of a person (euthanasia), and the writing of a prescription for drugs knowing that they will be used by a person to bring about the end of their own life (physician-assisted suicide).

To accurately assess the ethics and effects of a particular law or practice it is important that terminology is clear and unequivocal in what it describes. ‘Assisted dying’ for example may mean PAS, or EAS. On this point see:

For an ‘overview of the terminology, evolution and current legislative picture of assisted dying practices around the globe’ see:

Figure 3 below gives the name for the legislation allowing EAS in various jurisdictions.

|

Figure 3 |

Naming of the Act which allows EAS |

|

Belgium |

Belgian Euthanasia Act (2000) |

|

California |

End of Life Option Act |

|

Canada |

Medical Assistance in Dying Act (2016) |

|

Colorado |

End of Life Options Act (2016) |

|

DC |

Death With Dignity Act (2016) |

|

Hawai’i |

Our Care, Our Choice Act (2018) |

|

Luxembourg |

Loi sur L’Euthanasie et L’Assistance au Suicide (2009) |

|

Maine |

Death with Dignity Act (2019) |

|

Netherlands |

Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide Act (2002) |

|

New Jersey |

Death with Dignity Act (2019) |

|

Oregon |

Death with Dignity Act (1994) |

|

Vermont |

Patient Choice and Control at End of Life Act (2013) |

|

Washington |

Death with Dignity Act (2008) |

Extension of eligibility criteria for EAS

Following legalisation, legislation can extend eligibility from those terminally ill to other non-terminal conditions (children, mentally ill, etc.), see:

The logic of EAS eligibility for the terminally ill can be applied in the same way both to the chronically ill, and to justify non-voluntary euthanasia (i.e. for those incapable of requesting euthanasia). This is referred to as the ‘slippery slope’. See:

Keown, John. ‘Euthanasia in the Netherlands: Sliding down the Slippery Slope’. Notre Dame J.L. Ethics & Pub. Pol’y 9, no. 2 (1995): 407–48. * (full text available).

These concerns, including (among others) the EAS for psychiatric indications and evidence in practice of non-voluntary euthanasia are best considered by examining evidence from the four jurisdictions which the longest history of EAS: Switzerland (1982); The Netherlands (1984); Oregon (1997); and Belgium (2002).

Introduction

Assisted suicide in Switzerland is performed almost entirely through organisations such as EXIT and Dignitas. Since 1982 (when EXIT was founded) there have been only two official government reports, one in 2012 and another in 2014, and these are dependent on data provided by assisted suicide organisations. Media reporting of UK citizens dying in Switzerland plays a significant role in the UK debate, but it should be noted that most of those individuals would not qualify under current proposals for ‘Assisted Dying’, as they were not expected to die within six months. If the law changed in the UK either people would continue to go to Switzerland (which would have fewer restrictions) or the option of assisted suicide in Switzerland would place pressure on the UK to extend its practice to those who are not terminally ill. Research on the experience of assisted suicide in Switzerland is not reassuring.

In Switzerland, since 1942, inciting or assisting suicide has been illegal when it is for selfish motives (such as financial gain). Since 1982 this law has provided legal space for the organisation EXIT to promote assisted suicide for those ‘with unbearable symptoms or with unacceptable disabilities.’ There are two government reports from the Federal Statistical Office, one in 2012 and latest, for 2014, published in 2016 and revised in 2017. There are also statistics for assisted suicide by sex and age for 2003-2019, published by the Federal Statistical Office. Dignitas has released statistics from 1998-2021.

A systematic study of 43 consecutive cases of assisted suicide in Switzerland from 1992 to 1997 found that in 10 cases (23%), the time between first contact with EXIT and the completed assisted suicide was less than a week and in 4 cases (9%) it was less than a day. In 6 cases (14%) the person had previously been treated in a psychiatric institution. In 11 cases (26%) there was no serious medical condition recorded on file, and in 5 cases (12%) the stated reason for seeking assisted suicide was bereavement. The authors of the study conclude that in the 1990s assisted suicide was ‘performed by lay-people who act without outside control and violate their own rules’.

Frei, Andreas, et al. ‘Assisted suicide as conducted by a “Right-to-Die”-society in Switzerland: a descriptive analysis of 43 consecutive cases.’ Swiss Medical Weekly 131.25-26 (2001): 375-380. * (full text available).

A later study found that between the 1990s and 2001-2004 the rate of assisted suicide for non-fatal diseases increased from 22% to 34% and concluded that ‘weariness of life rather than a fatal or hopeless medical condition may be a more common reason for older members of Exit Deutsche Schweiz to commit suicide’.

Fischer, S., Huber, C.A., Imhof, L., Imhof, R.M., Furter, M., Ziegler, S.J., Bosshard, G. ‘Suicide assisted by two Swiss right-to-die organisations’. Journal of Medical Ethics 34, no. 11 (2008): 810-814. * (full text available).

A study in 2014 found that assisted suicide in Switzerland was associated with living alone and divorce and was significantly more frequent among women. In 16% of deaths by assisted suicide no medical condition was listed.

Research on trends from 1991 to 2008 showed ‘a tripling of assisted suicide rates in older women, and the doubling of rates in older men’.

Between 2009 and 2019, the number of assisted suicide deaths increased from 297 to 1196 (an increase of over 400%).

Research showed that requests for assisted suicide were not based on symptom burden but on fear of loss of control. Moreover, those seeking assisted suicide had misconceptions about palliative care.

Until 2006 assisted suicide had not occurred in Switzerland in a hospital setting. The difficulties of introducing it into hospital and the concerns of the palliative care team are set out below.

There is also research from Switzerland on the negative impact on family members of witnessing assisted suicide.

Assisted suicide in Switzerland is most well known in the UK because of people travelling from the UK to die by assisted suicide. A detailed study of ‘suicide tourism’ shows numbers are increasing, the proportion of cancer is decreasing and the proportion of mental illness and multiple co-morbidities is increasing. Among reasons for assisted suicide the largest single cause, with 223 cases, was cancer, but 37 cited Parkinson’s disease, 37 gave arthritis as a reason, 14 cases were for mental illness, and 40 gave as a reason impairment of eyesight and/or hearing.

A study from 2016 shows that there has been an increase in the practices of voluntary and non-voluntary euthanasia in Switzerland, which are both illegal. Additionally, there has been a ‘substantial increase in the use of continuous deep sedation until death, from 4.7% of all deaths in 2001 to 17.5% in 2013 [...] this practice was therefore more common in Switzerland than in either Belgium (12.0% in 2013) or the Netherlands (12.3% in 2010)’.

Introduction

In addition to annual reports, based on notified cases of euthanasia there have been a series of studies of end-of-life practices at 5-year intervals since 1990. These were nationwide studies of a stratified sample from the national death registry. Questionnaires were sent to physicians attending these deaths and were returned anonymously. The first is commonly termed the Remmelink Report and subsequent reports followed the same pattern. Both the annual reports and the five yearly studies show incremental increases in deaths by euthanasia over time. Deaths by assisted suicide are less frequent, in part because they are associated with complications.

In the Netherlands euthanasia was effectively decriminalised by a court decision in 1984. This was the basis of a legal statute in 2001 legalising euthanasia and physician assisted suicide. Since 2002 the Netherlands has produced an annual report on the cases notified to the five regional euthanasia committees. These are available (in English once the year is selected).

The first two reports showed evidence of a number of deaths without explicit patient request (in other words non-voluntary euthanasia). The rates were 0.8% and 0.7% being equivalent to 1,000 and 900 deaths in per year. The reaction of supporters was generally to dismiss the significance of these figures, rather than to see them as a possible cause for concern.

Keown, John. ‘Euthanasia in the Netherlands: Sliding down the Slippery Slope’. Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy 9, no. 2 (1 January 2012): 407-448. * (full text available).

Cohen-Almagor, Raphael. ‘Non-Voluntary and Involuntary Euthanasia in the Netherlands: Dutch Perspectives’. Issues in Law & Medicine 18 (2003): 239-257. * (full text available).

For such reasons the law and practice of euthanasia and assisted suicide in the Netherlands has been criticised several times by the United Nations Human Rights Committee.

The 2019 report expresses its concern by stating ‘The Committee is concerned, however, at the limited ex ante review of decisions to terminate life, including the legal and ethical implications of such decisions (art. 6)’. (para. 28). See:

Results from the most recent 5-yearly study (published in 2017 and providing data from 1990, 1995, 2001, 2005, 2010 and 2015) show that deaths classified as ‘ending life without explicit patient request’ have declined from 0.8% in 1990 0.3% in 2015. However, overall numbers of deaths by euthanasia have almost tripled (from 1.7% to 4.5%) Another matter of concern is the steep rise in cases of continuous deep sedation (from 8.2% in 2005to 18.3% in 2015), which is in addition to the rise in deaths by ‘intensified alleviation of symptoms’ (from 18.8% of deaths in 1990 to 35.8% of deaths in 2015). The presence of so many deaths with, or by, continuous deep sedation or drugs for intensified alleviations of symptoms confounds the data as either may be used as equivalent to (voluntary) euthanasia or to life ending without request. See:

The latest annual report (for 2020) shows that the total number of deaths by euthanasia continues to increase. There were 6,938 deaths by euthanasia or assisted suicide notified in 2020, up 9.1% on the previous year, and constituting 4.1% of all deaths in the Netherlands for 2020 (which must be taken in conjunction with the fact that there was an excess of around 15,000 deaths in the Netherlands in 2020). In 2 cases, coronavirus infection was the grounds for euthanasia, and coronavirus infection plus other medical conditions in a further 4 cases.

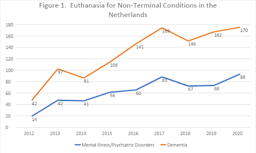

There are no data on euthanasia for either mental illness or dementia prior to 2012 (before this they are presumably considered under ‘other conditions’). In the 2013 report the category is changed from ‘mental illness’ to ‘mental disorders’, and from 2014 on is referred to as ‘psychiatric disorders’. Figure 1 (data source) below shows the figures for these conditions.

From 2012-2020 euthanasia for psychiatric disorders has increased by over 600% and for dementia by over 400%.

This increase in euthanasia or assisted suicide for non-terminal conditions reflects opinion among professionals, with a significant number (between 24% and 39%) in favour of euthanasia or assisted suicide for individuals who experience mental suffering due to loss of control, chronic depression or early dementia. A third of doctors and 58% of nurses were in favour of euthanasia in the case of severe dementia, given the presence of an advance directive.

Kouwenhoven, Pauline SC, Natasja JH Raijmakers, Johannes JM van Delden, Judith AC Rietjens, Maartje HN Schermer, Ghislaine JMW van Thiel, Margo J Trappenburg, et al. ‘Opinions of Health Care Professionals and the Public after Eight Years of Euthanasia Legislation in the Netherlands: A Mixed Methods Approach’. Palliative Medicine 27, no. 3 (1 March 2013): 273-80. * (post print text available).

Other research shows a wide variation among general practitioners, consultants and members of the euthanasia committees in their judgement of whether the patient’s suffering is sufficient for euthanasia.

While euthanasia is defined as ending life on request, the Netherlands has extended life ending without request to newborn infants with disabilities. A description of the protocol (known as the Groningen protocol) is given by two authors who helped develop this practice.

Verhagen, A. A. E., and P. J. J. Sauer. ‘End-of-Life Decisions in Newborns: An Approach From the Netherlands’. Pediatrics 116, no. 3 (1 September 2005): 736–39. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0014. * (full text available).

While euthanasia and assisted suicide are requested to secure an easeful death, complications are well documented, especially in assisted suicide. A study in 2000 found that ‘complications [such as spasm, gasping for breath, cyanosis, nausea or vomiting] occurred in 7% of cases of assisted suicide, and problems with completion [a longer-than-expected time to death, failure to induce coma, or re-awakening of the patient] occurred in 16%’ because of which ‘physicians who intend to provide assistance with suicide sometimes end up administering a lethal medication themselves.’ This is not only a problem of the past; in the 2020 report there were 6,705 cases of euthanasia (‘termination of life on request’), 216 cases of assisted suicide and 17 cases involving a combination of the two (i.e., cases which began as assisted suicide, but had to be completed by euthanasia).

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200002243420805. * (full text available).

Lastly, euthanasia is possible above the age of 12 and below the age of 1. But in 2020, the Netherlands Paediatric Association (Nederlandse Vereinging voor Kindergeneeskunde) expressed the position that the law be extended to allow the termination of life of children between the ages of 1 and 12 under certain conditions. See also the letter to parliament by Hugo de Jonge, the former Minister of Health, Welfare and Sport.

Introduction

The most important evidence for practice in Oregon is provided by annual reports on the Death with Dignity Act. This section also highlights some aspects that been raised in relation to Oregon practice but are not based on the reports. See also research on the impact of assisted suicide on suicide prevention (section 7, below).

Oregon legalised physician assisted suicide in 1997 and produces annual reports. Helpfully the latest report (2021) includes data from previous years. Note that the figure for the number of deaths in the most recent year covered by the report will generally be inaccurate as deaths are recorded against the year of the lethal prescription. For example, if a lethal prescription given in 2012 were used in 2013 the death would be recorded as due to assisted suicide in the 2012 figures. Reports from all individual years can be accessed here.

According to the latest official Oregon report, the most frequent end-of-life concern cited by people requesting assisted suicide is not pain but ‘loss of autonomy’ (90.9%), followed by decreased ability ‘to engage in activities making life enjoyable’ (90.2%), ‘loss of dignity’ (73%), ‘burden on family, friends/caregivers’ (48.3%), and ‘losing control of bodily functions’ (43.7%) and only then ‘inadequate pain control or concern about it’ (27.5%), (in each case citing accumulated data for 1998-2021). Evidently, most of these concerns relate to disability and increased dependence. The concern about feeling one is a ‘burden’ on others is significant, much more so than fear of pain (which, also, should not be conflated with actual pain).

From the same report it is clear that in only 14.6% of cases was the prescribing physician present at the time of death (only 11.6% in 2020), that only 3.3% were referred for psychiatric evaluation (only 0.8% in 2021), and that in 56.7% of cases the person was dependent on Medicare/Medicaid insurance or other governmental insurance (up to 78.9% in 2021).

According to Oregon’s Prioritized List of Health Services 2022 cancer treatment is limited according to relative life expectancy, for example, ‘[t]reatment with intent to prolong survival is not a covered service for patients who have progressive metastatic cancer [...]’(Guidance Note 12, GN-5). In contrast ‘It is the intent of the Commission that services under ORS 127.800-127.897 (Oregon Death with Dignity Act) be covered for those that wish to avail themselves to those services’ (Statements of Intent, SI-1).

[N.B. The Statements of Intent and Guidance Notes come after the 160 pages of the prioritised list.]

Health Evidence Review Commission, Prioritized List of Health Services (1 January 2022).

It should be noted that the drugs that are used for assisted suicide are also used in execution by lethal injection in the United States. This dual use is causing availability problems with supply of the drugs.

Jaquiss, Nigel. ‘Penalized By The Death Penalty’ Willamette Week 21 May 2014.

A good overview of practice in Oregon, including some case studies as well as statistical evidence, shows problems with doctor shopping, suspect coercion and lack of sufficient psychiatric evaluation.

Hendin, Herbert, and Kathleen Foley. ‘Physician-Assisted Suicide in Oregon: A Medical Perspective’. Michigan Law Review 106, no. 8 (2008): 1613–39. * (full text available).

Kenneth Stevens has shown that from 2001 to 2007 a majority (61%, 165 out of 271) of the lethal prescriptions were written by a minority (18%, 20 out of 109) of the participating physicians. More striking still, just 3 physicians were responsible for 23% of lethal prescriptions (62 out of 271).

See also ‘Five Oregonians to Remember’ PCCEF, 27 December 2007.

Introduction

Though Belgium legalised euthanasia in 2002, eighteen years after the Netherlands (in 1984), its number of deaths are near that of the Netherlands. There were 5,015 reported cases in 2019 (more than six times the 822 reported cases in 2009). According to research conducted by Chambaere (see below) these official figures underreport euthanasia by around 50%. What is more worrying is that research indicates that more than 1,000 patients a year (1.7% of all deaths) have their lives ended deliberately without having requested it. This figure has not declined with time. Since legalisation in 2002, reports have been produced every two years. These are available (in French) here.

For a critical analysis of euthanasia in Belgium, see:

Jones, David Albert, Chris Gastmans, and C. MacKellar, eds. Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide: Lessons from Belgium. Cambridge Bioethics and Law. Cambridge, UK and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2017. (This book can be ordered here).

Belgian law came to prominence with the decision in February 2014 to extend euthanasia to children. This caused concern among clinicians and bioethicists in other countries.

Carter, Brian S. ‘Why Palliative Care for Children Is Preferable to Euthanasia’. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine® 33, no. 1 (1 February 2016): 5–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909114542648. * (full text available).

For background to the original 2002 law and its initial implementation see:

Cohen-Almagor, Raphael. ‘Euthanasia Policy and Practice in Belgium: Critical Observations and Suggestions for Improvement’. Issues in Law & Medicine 24, no. 3 (2009): 187–218.* (full text available)

See also a report analysing ten years of euthanasia practice in Belgium.

Research shows that the cases that are not reported are also less likely to involve a written request, less likely to involve specialist palliative care, and more likely to be performed by a nurse.

Research on nurses in Belgium in 2007 showed that cases of life-ending without request were almost as common as cases of euthanasia, and that in 12% of euthanasia cases and 45% of life-ending without request it was a nurse who administered the lethal dose, actions which went ‘beyond the legal margins of their profession’.

On the ongoing issue of high levels of intentional life-ending without consent in Belgium see:

Cohen-Almagor, Raphael. ‘First Do No Harm: Intentionally Shortening Lives of Patients Without Their Explicit Request in Belgium’. Journal of Medical Ethics, 4 June 2015. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2614587. * (full text available).

Research has also shown that, in Belgium, continuous deep sedation is used with the intention or co-intention to shorten life in 17% of cases, but that it is rarely instituted at the request of the patient (only in 12.7% of cases).

Recent research (published in 2015) shows that while rates of euthanasia increase there has been no improvement in reporting and no reduction in cases of life-ending without request.

In the face of evidence of widespread ending of life without request some researchers have sought to excuse these actions because a third of such patients had, ‘at some point’ in the past, either explicitly or ‘implicitly’ expressed a wish that their lives be ended. However, the very attempt to downplay concerns about deaths deliberately brought about without an explicit request itself illustrates the degree to which non-voluntary euthanasia in Belgium is tolerated and is not regarded as shocking or as a practice in urgent need of correction.

On the distinction between expressing a wish to die, a wish to hasten death, and a request, see:

Data from the annual reports shows that an increasing percentage of those dying by euthanasia mention a combination of physical and psychical suffering (78.8% in 2018 and 82.8% in 2019), with figures for solely physical pain reducing (17.7% in 2018 and 12.8% in 2019) and suffering for solely psychic reasons increasing (3.5% in 2018 and 4.3% in 2019).

Stories of individual cases are no substitute for quantitative research, but they help show the possible human meaning behind these statistics. Some illustrative examples are given below.

‘Marc and Eddy Verbessem, Deaf Belgian Twins, Euthanized’ The World Post 15 January 2013.

E O’Gara ‘Physically healthy 24-year-old granted right to die in Belgium’ Newsweek 29 June 2015.

Further example cases from Belgium are described here:

Introduction

Groups representing people with disabilities have been at the forefront of opposition to the legalisation of assisted suicide and euthanasia. Arguments from this perspective, especially in popular publications and comment pieces, have been criticised as reflecting and/or feeding on fears without showing that these fears are reasonable. However, there is also more critical reflection from this perspective, including discussion of empirical evidence relevant to assessing these concerns.

Some opinion polls among disabled people find considerable support for legalising ‘assisted dying’.

These results are similar to opinion polls in the general population and should be treated with the same caution (see above on the wording of polls). It is important also to take into account polls that identify concerns among disabled people that legal changes could put pressure on disabled people to end their lives prematurely.

An interesting exchange on this issue by two people with disabilities was conducted by Carol Gill and Andrew Batavia. Batavia argues that empirical data is irrelevant to the issue which, in his view, is about values, and centrally the value of autonomy. He is in favour of legalising assisted suicide.

In response Gill presents data, which is relevant to the perception of disability and its role (implicitly or explicitly) in decisions to grant requests for assistance in suicide. For example, she cites research that shows that among 153 emergency care providers, only 18% of physicians, nurses, and technicians imagined they would be glad to be alive with a severe spinal cord injury. In contrast, 92% of a group of 128 persons with high-level spinal cord injuries said they were glad to be alive.

Unfortunately, neither of these papers is freely available online. However, another very interesting paper by Gill provides a good sense of what a critical and empirically informed disability perspective looks like. More generally, the Disability and Health Journal (in which this paper appears) is a useful source for articles on disability and assisted suicide.

Gill, CJ. ‘No, we don't think our doctors are out to get us: Responding to the straw man distortions of disability rights arguments against assisted suicide’. Disability and Health Journal 3.1 (2010): 31-38. * (full text available)

Probably the most influential article arguing that the evidence shows no negative impact of assisted suicide or euthanasia on vulnerable groups (including people with disabilities) is by Margaret Battin.

The methodology and conclusions of this paper have been criticised by Ilora Finlay and Rob George.

Finlay, I. G., and R. George. ‘Legal Physician-Assisted Suicide in Oregon and The Netherlands: Evidence Concerning the Impact on Patients in Vulnerable Groups--Another Perspective on Oregon’s Data’. Journal of Medical Ethics 37, no. 3 (March 2011): 171–74. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2010.037044. *

A detailed discussion of Battin’s evidence and counter-evidence from other expert witnesses is found in the Irish Divisional Court case Fleming v Ireland [2013] IEHC 2 (especially para 67).

‘[T]he the expert evidence offered by Dr. O’Brien and Professor George to the effect that relaxing the ban on assisted suicide would bring about a paradigm shift with unforeseeable (and perhaps uncontrollable) changes in attitude and behaviour to assisted suicide struck the Court as compelling and deeply worrying… The Court finds the evidence of these witnesses, whether taken together or separately, more convincing than that tendered by Professor Battin, not least because of the somewhat limited nature of the studies and categories of person studied by Professor Battin…’

Battin’s argument is also criticised by Pereira on the basis that “safeguards” are largely illusory.

Pereira, J. ‘Legalizing Euthanasia or Assisted Suicide: The Illusion of Safeguards and Controls’. Current Oncology 18, no. 2 (April 2011): e38. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.v18i2.883. * (full text available).

Similarly, a detailed discussion of the evidence from Oregon from a disability perspective concludes that ‘Battin et al.’s interpretation that people with physical disabilities or chronic illnesses are not at increased risk for DWD does not seem to be supportable given available data’.

CE Drum, G White, G Taitano and W Horner-Johnson, ‘The Oregon Death with Dignity Act: results of a literature review and naturalistic inquiry’. Disability and health journal, 2010, 3(1): 3-15. * (full text available).

If disability includes mental illness, then there is clearly a group of patients who are prima facie endangered by assisted suicide. In Oregon there has been a decline in the “safeguard” of referral for psychiatric evaluation whereas in Belgium and Switzerland mental illness can itself be a basis for euthanasia or assisted suicide. A study published in the BMJ shows how far the euthanising of psychiatric patients has progressed in Belgium: of 100 patients who requested euthanasia for psychiatric reasons, 73 ‘were medically unfit for work (they were either receiving disability living allowances or had taken early retirement)’, i.e. most were categorised as having a disability. Of the 100, 38 were referred for further psychiatric evaluation, after which 17 were approved for euthanasia and 10 died by euthanasia during the study period. Of the 62 people not referred, 31 were approved for euthanasia and 25 died by euthanasia during the study period. These patients suffered from a variety of conditions including mood disorders (58 including 10 who were bipolar), borderline personality disorder (27), schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (14), post-traumatic stress disorder (13), eating disorders (10), autism spectrum disorder (7), attention deficit hyperactivity (1) as well as other diagnoses, often combining diagnoses (e.g., a mood disorder and personality disorder). During the period of the study 6 participants died by (non-assisted) suicide, one from anorexia nervosa and one from palliative sedation. None were terminally ill.

Disability makes assessment of ‘decisional capacity’ difficult. A study of cases in the Netherlands shows that the ‘Dutch EAS due care criteria are not easily applied to people with intellectual disabilities and/or autism spectrum disorder, and do not appear to act as adequate safeguards.’ See:

Tuffrey-Wijne, Irene et al. “‘Because of His Intellectual Disability, He Couldn’t Cope.’ Is Euthanasia the Answer?”. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, vol. 16, no. 2 (June 2019):113-116, https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12307 * (post-print draft version available).

EAS in the Netherlands for psychiatric disorders shows that patients are ‘mostly women, of diverse ages, with complex and chronic psychiatric, medical, and psychosocial histories’. See:

Kim, Scott Y H et al. “Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide of Patients With Psychiatric Disorders in the Netherlands 2011 to 2014.” JAMA Psychiatry vol. 73,4 (2016): 362-8. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2887 * (full text available).

Concern is also expressed over safeguards for the disabled, stemming from the myriad of problems the disabled face, such as ‘subtle pressure, despair at living in a world where their daily existence is seen as one of inevitable suffering or, exhaustion from fighting for the accommodations required to live a life of dignity and pursue their chosen lifestyle and purposes’. See:

Stainton, Tim. “Disability, vulnerability and assisted death: commentary on Tuffrey-Wijne, Curfs, Finlay and Hollins.” BMC Medical Ethics vol. 20,1 89. 27 (Nov. 2019), doi:10.1186/s12910-019-0426-2 * (full text available).

With respect to more recent developments in Canada regarding EAS for mentally ill patients, see:

On the changing social attitude to those living with dementia and how euthanasia poses a threat to living and dying well with dementia, see:

Introduction

Sometimes advocates of assisted suicide are happy to use this terminology, as for example in the ‘Assisted Suicide (Scotland) Bill’ (introduced in 2011), which was rejected by the Scottish Parliament in 2015. Other proponents avoid this language and prefer ‘dying / death with dignity’, ‘assisted dying/death’ or ‘medical aid in dying’. However, evidence indicates no sharp distinction between assisted suicide and non-assisted suicide. Evidence also suggests legalising assisted suicide ‘normalises’ suicide and is associated with increases in suicide.

Evidence from the USA shows that the legalisation of ‘assisted suicide is associated with a significant increase in total suicide (inclusive of assisted suicide) and no reduction in non-assisted suicide.’

Jones, David Albert and David Paton ‘How does legalization of physician-assisted suicide affect rates of suicide?, Southern Medical Journal, 108.10 (2015): 599-604. * (pre-print draft available).

The association of legalising assisted suicide and a ‘significant increase in total suicides’ is also supported by more recent research on data from the USA. Paton and Sourafel also conclude that ‘[i]t is possible that there is some substitution from unassisted suicide to assisted suicide but that this is balanced out by an increase in unassisted suicide arising from, for example, a reduction in societal taboos associated with suicide’. See:

Sourafel, Girma, and David Paton. ‘Is Assisted Suicide a Substitute for Unassisted Suicide?’ European Economic Review, 9 April 2022, 104113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2022.104113. * (pre-proof text available).

In Europe, the introduction of euthanasia and assisted suicide has resulted in ‘considerable increases in suicide (inclusive of assisted suicide) and in intentional self-initiated death’. See:

Jones, David Albert. ‘Euthanasia, Assisted Suicide, and Suicide Rates in Europe’, Journal of the Ethics of Mental Health 11 (2022):1-35. * (full text available).

Restricting access to means of suicide appear to be ‘particularly effective in contexts where the method is popular, highly lethal, widely available, and/or not easily substituted by other similar methods’. See:

It is argued that ‘assisted death’ of a kind legalised in Oregon, is not assisted suicide because (1) with ‘assisted death’ the person is terminally ill and (2) (non-assisted) suicide is typically the result of depression. However, according to one UK study, ‘at least 10 percent of [non-assisted] suicides nationally involve[ed] some form of serious physical illness (either chronic or terminal)’. See:

Bazalgette, L., W Bradley, J Ousbey. The Truth about Suicide (London: Demos, 2011)

Similarly in Switzerland ‘In 53% of cases, causes of death registrations for [non-assisted] suicide do not contain any information about concomitant diseases. If no information is available, this may mean various things: either no disease was present or it was unknown. If information is available, 56% of entries cite depression. In the remaining 44% of entries, a physical disease is mentioned. Physical diseases include a range similar to that of assisted suicide (G11).’ (emphasis added)

Similarly, a report on suicide in Oregon found that 25% of men and 26% of women who died by suicide had had physical health problems, and in the over-65 cohort, 66% of men and 56% of women had physical health problems, including conditions such as cancer, heart disease, and chronic pain.

The vulnerability of older people, those living alone and those with physical illness was highlighted in a report by the New York Task Force in 1994. The Task Force also found that depression was prevalent in this population, but largely undiagnosed and untreated (see especially chapter 2 of the report).

Similarly, in a study of 178 Compassion & Choices clients, of those who, in the study period, obtained lethal medication 3 out of 18 (17%) fulfilled the criteria for depression and of those who died by assisted suicide by the end of the study 3 out of 9 (33%) met the criteria for depression.

It has been argued that legalising assisted suicide could, paradoxically, delay or inhibit suicide. This has been argued by Lord Falconer and others, but a particularly clear statement is provided by EXIT.

However, in Oregon between 1999 (two years after PAS was introduced) and 2010 the suicide rate among those aged 35-64 increased by almost 50% (compared to 28% nationally).

See also the report on high rates of suicide in Portland, Oregon. This increase is without counting assisted suicides, which rose in Oregon by 44% in 2013 alone.

According to the Swiss government report, ‘From 1995 to 2003, the absolute number of suicides fell considerably. Since then, it has more or less remained stable while cases of assisted suicide have increased considerably since 2008 in particular. In 2014, for 7 cases of suicide observed, 5 cases of assisted suicide were seen (G7)’.

Determination of eligibility for EAS may also have an effect on vulnerability. Looking at the situation in Canada, Isenberg-Grzeda et al conclude that ‘Clinicians must be vigilant and prepared for the possibility of heightened risk, including risk of self-harm, after a finding of ineligibility for assisted death’. See:

It must be noted that if suicide follows on from a determination of ineligibility for EAS, that person’s death would be considered suicide. However, it would not be considered ‘suicide’ if he or she had been eligible and died as a result of the provision of EAS. This highlights the broader point that euphemistic expressions such a ‘assisted dying’ or ‘medical aid in dying’ simply rename what is correctly termed ‘suicide’.

Suicide Contagion

A Swiss study indicates evidence for suicide contagion following media reports of assisted suicide:

Research on the impact of reporting assisted suicide in Oregon has also suggested such an effect.

Stark, Paul. ‘Assisted suicide and contagion’ MCCL White Paper, May 2015.

This evidence coheres with what is known about suicide, that it increases if the means are more widely available and if it is normalised, see for example, Euregenas (European Regions Enforcing Actions Against Suicide) Suicide Prevention Toolkit for Media Professionals.

Evidence of suicide rates among veterinarians (which are significantly higher than the average among the population) is generally understood to be due to access to lethal drugs.

Research also shows that positive ‘suicide role models’ reinforce high rates of suicide in a population:

Werther and Papageno Effects

Suicides are also associated with the way that suicide is presented in the media. The ‘Werther effect’ refers to media presentations of suicides (fictional and real) and their effect on an increase in suicide rates. The ‘Papageno effect’ refers instead to the preventative effect of media portrayals which depict people coping despite difficult life circumstances and suicidal ideation.

A survey of studies on the two effects shows that ‘suicide contagion is more likely to occur after extensive media coverage with a content rich in positive definitions of suicide’. Factors that increase the likelihood of imitation are, for example, ‘the celebrity status of the suicide victim, similar demographic characteristics and the media audience, and media reports on a new suicide method’. At the same time, different media portrayals can ‘have an educative or preventative effect and can reduce the risk of contagion’. See:

Domaradzki, J. ‘The Werther Effect, the Papageno Effect or No Effect? A Literature Review’. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 5 (1 March 2021): 2396. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052396. * (full text available).

Studies of the Werther and Papageno effects focus on media portrayals of suicide, but ‘[g]uidance is needed for media reporting of assisted suicide’ as well. See:

Jones, David Albert. ‘Assisted dying and suicide prevention’ Journal of Disability & Religion, 22.3 (2018): 298-316. * (pre print text available online).

A 2021 survey of members of the Association for Palliative Medicine of Great Britain and Ireland showed that ‘There is also a significant degree of frustration at the media narrative regarding end of life care, which clinicians view as being driven by assisted suicide lobbying. There is concern that poor portrayal of palliative care in the media has led patients and families to have a skewed understanding of palliative care, and there is fear that patients are in a position of ignorance at a vulnerable moment in their lives’.

Introduction

Proponents of a change in the law frequently invoke choice (for example the US organisation ‘Compassion & Choices’ or the Scottish organisation ‘My Life, My Death, My Choice’). This language is very similar to ‘pro-choice’ language in relation to abortion, and so it might seem that feminists who are in favour of increased access to legal abortion would also support legalisation of EAS. This argument is indeed accepted by some feminists; however, it has been challenged by a number of feminists who argue that EAS would have a disproportionately negative impact on women.

Wolf argues that a legal right to abortion (which she supports) does not imply a legal right to assisted suicide.

On this point see also:

Spindelman, Marc. ‘Are the Similarities between a Woman’s Right to Choose an Abortion and the Alleged Right to Assisted Suicide Really Compelling?’ U. Mich. J. L. Reform 29, no. 775 (1996): 775-856. * (full text available).

Whereas, in the West, the rate of suicide is much higher among men than women (roughly four times), PAS (in Oregon and Washington) is roughly equal between men and women, and rates of assisted suicide in Switzerland reveal a higher proportion of women; this is also true of the suicides assisted by Kervorkian.

Kohm, Lynne Marie, and Britney N. Brigner. ‘Women and Assisted Suicide: Exposing the Gender Vulnerability to Acquiescent Death’. Cardozo Women’s Law Journal 4 (1997): 241. * (full text available).

See also:

It has also been argued that a feminist account of relational autonomy gives more ground to be cautious about permitting assisted suicide.

See also:

For a study of the larger number of women who receive EAS for a psychiatric condition in Belgium and the Netherlands, and its relation to questions of suicide prevention, see:

Data from Switzerland demonstrates not only an increase in total assisted suicides year on year, but also the disproportionately large number of women dying by assisted suicide.

Whichever side of the argument you find more cogent, it is useful to look at the opposite view and the counter-arguments and evidence they produce, such as it is. Campaign organisations are, by their nature, one sided, but at the very least they raise questions and identify some relevant evidence.

Organisations in favour of legalising assisted suicide or euthanasia

In 2005 the Voluntary Euthanasia Society (founded 1935) changed its name to ‘Dignity in Dying.’ Its immediate aim is legalising physician assisted suicide for the terminally ill not, currently, euthanasia.

http://www.dignityindying.org.uk/

In 2009 Michael Irwin left the Dignity in Dying to found the Society for Old Age Rational Suicide which campaigns for assisted suicide for people who are not dying, but are tired of living. In 2015, the organisation changed its name to ‘My Death, My Decision’.

https://www.mydeath-mydecision.org.uk/

The largest organisation in the USA to campaign in favour of assisted suicide is Compassion & Choices (successor to the Hemlock Society which was founded in 1980).

http://www.compassionandchoices.org/

Also founded in 1980, The World Federation of Right to Die Societies no longer counts Dignity in Dying or Compassion & Choices as ‘members,’ but has links to them as ‘other right to die societies’.

EXIT founded in 1982 is the main organisation that arranges assisted suicide for Swiss citizens.

Organisations opposed to legalising assisted suicide and euthanasia

Founded in 2005, Care Not Killing is a UK-based alliance of individuals, disability and human rights groups, healthcare providers, and faith-based bodies opposed to assisted suicide and euthanasia.

http://www.carenotkilling.org.uk/

In 2021 the Better Way campaign was founded to oppose assisted suicide and to set out a positive, alternative vision for the UK. Its website contains information about the Canadian experience of euthanasia and assisted suicide.

https://www.betterwaycampaign.co.uk/canada/

The Euthanasia Prevention Coalition (EPC) has an international scope. There is also a European arm.

For a disability perspective see Not Dead Yet and the rather more British (and understated) Not Dead Yet UK.

For an American perspective critical of assisted suicide see the websites of Physicians for Compassionate Care Education Foundation, the Patients’ Rights Council and ‘Choice’ is an Illusion.

https://www.patientsrightscouncil.org/site/

https://www.choiceillusion.org/

News and comment

The excellent and free bioethics news service Bioedge frequently includes stories on these issues.

https://bioedge.org/end-of-life-issues/euthanasia/

Alex Schadenberg (chair of EPC) has a blog, which is also very useful for news stories.

https://alexschadenberg.blogspot.co.uk/

Living and dying well is not a campaign organisation, but presents research and analysis of evidence relevant to (and critical of) assisted suicide and euthanasia.

https://www.livinganddyingwell.org.uk/

Further academic resources

This guide is intended only as an introduction to some of the resources for assessing the evidence and arguments for and against assisted suicide and euthanasia. It is, of necessity, selective as there are many hundreds of official reports, legal cases and journal articles on these topics. Students should research independently making use of academic indices and databases such as EBSCO, Lexis Nexis, Philosophers’ Index, PhilPapers and MEDLINE. You should also ‘follow the footnotes’ reading the sources invoked by or criticised by the article you are reading.

The search engine Pubmed gives access to the MEDLINE database, which includes very many medical journals and also journals of medical ethics, and medically related humanities and social sciences. Unlike other indices it is freely accessible and is a good place for the non-specialist to begin more serious research.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed

Anscombe Bioethics Centre Briefing Papers

Beuselinck, Benoit. ‘Euthanasia Case Studies from Belgium: Concerns About Legislation and Hope for Palliative Care’. Briefing Papers: Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide. Oxford: The Anscombe Bioethics Centre, 2021.

Jones, David Albert. ‘Defining the Terms of the Debate: Euthanasia and Euphemism’. Briefing Papers: Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide. Oxford: The Anscombe Bioethics Centre, 2021.